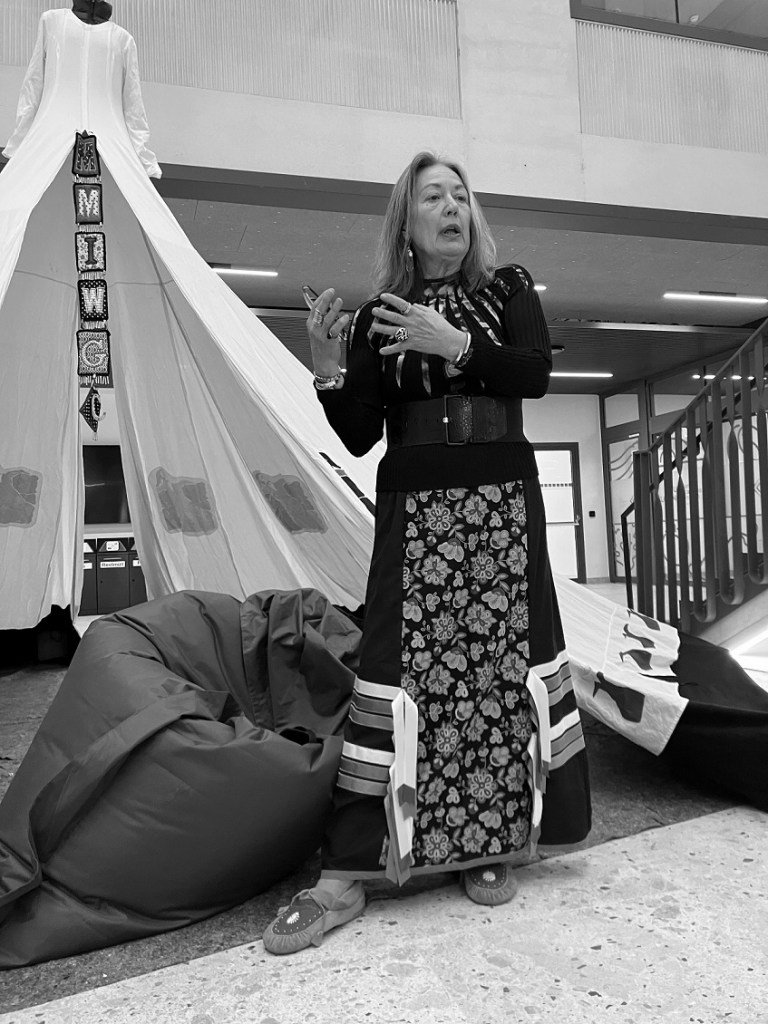

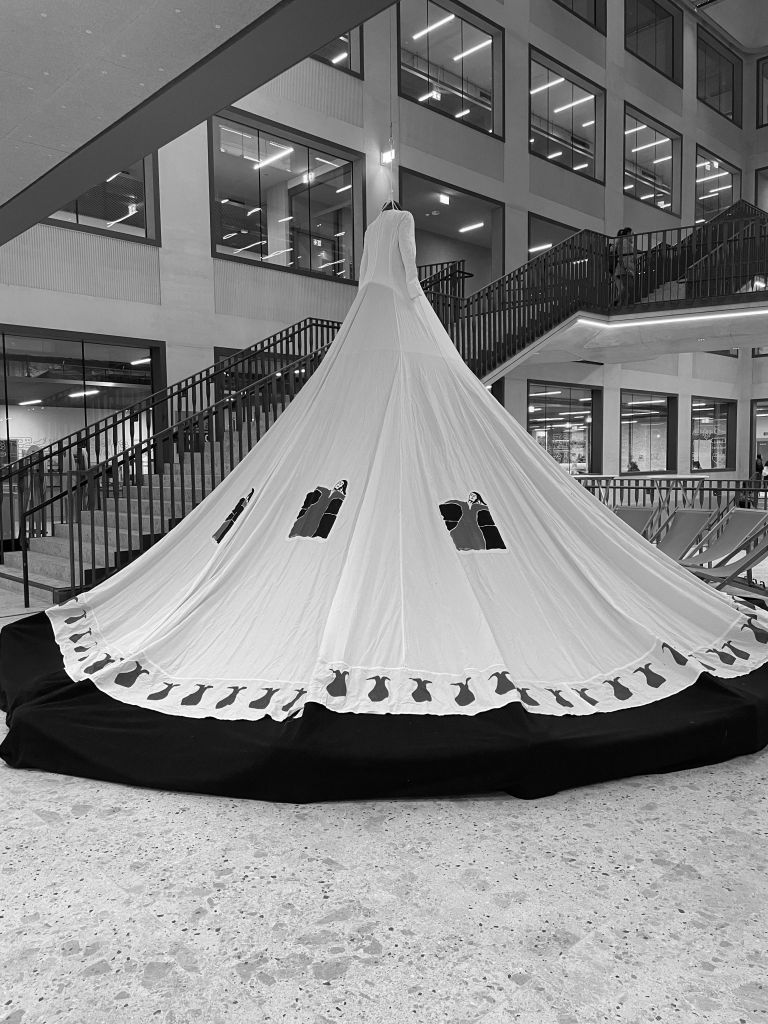

Wer am 28. und 29. November durch den Eingang des Ágnes-Heller-Hauses trat, dem bot sich ein besonderer Anblick: Im Foyer des frisch eröffneten Universitätsgebäudes thronte ein ausladendes Tipi mit roten Aufdrucken, befestigt an einer Figur, die oberhalb davon zu schweben schien. Rundherum verteilt waren große Sitzkissen, Liegestühle und Stehtische platziert. Ein einladender Ort zum Verweilen – aber auch einer, mit dem die Künstlerin Heather Carroll auf eine düstere Geschichte aufmerksam machen will. Das komplex hat die Künstlerin getroffen.

Das Kunstprojekt „La Robe Rouge“ der kanadisch-luxemburgischen Künstlerin Heather Carroll gliedert sich ein in das Red-Dress-Movement und hat zum Ziel, auf die verschwundenen und ermordeten Indigenen Mädchen und Frauen („Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women“ – MMIW) aufmerksam zu machen. Die Ausstellung fand großen Anklang bei Interessierten, Teilnehmer:innen aus Universität und Schulen sowie Passant:innen, die im Vorbeigehen auf die Installation aufmerksam wurden und nähertraten, um sich darüber zu informieren. Organisiert wurde die Ausstellung in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Zentrum für Kanadastudien der Universität Innsbruck, insbesondere dessen Leiterin Doris Eibl. Die Veranstaltung steht auch im Zeichen der internationalen Kampagne „16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence“, die jährlich von 25. November (Internationaler Tag zur Beseitigung von Gewalt gegen Frauen) bis 10. Dezember (Tag der Menschenrechte) andauert.

Das rote Kleid und die Gewalt

Ausgangspunkt für das Red-Dress-Movement ist das seit 2010 bestehende Kunstprojekt REDdress der Métis-Künstlerin Jaime Black. Es zeigt rote Kleider, die in unterschiedlichen Umgebungen hängen. Die „leeren“ Kleider repräsentieren dabei die verschwundenen und ermordeten Indigenen Mädchen und Frauen, die diese eigentlich tragen sollen. Symbolisch steht die Farbe Rot für die einzige Farbe, die von Geistern gesehen werden kann, die roten Kleider sollen also deren Geister rufen.

Das „Red Dress“ ist inzwischen zu einem geflügelten Begriff geworden und prangert gemeinsam mit dem Red-Dress-Day am 5. Mai die Missstände im Hinblick auf die Gewalt gegen Indigene Frauen in Kanada und den USA an. Die Viktimisierung dieser Gruppe ist die Folge jahrhundertelanger Ausbeutung, sozialer, wirtschaftlicher und politischer Marginalisierung sowie von Rassismus und Sexismus. Verschiedene Berichte, beispielsweise ein Bericht der US Commission on Civil Rights von 2018, ergeben, dass die Wahrscheinlichkeit Indigener Mädchen und Frauen in Nordamerika, in ihrem Leben Opfer von Gewalt werden, um ein Vielfaches höher ist als bei Frauen anderer Ethnien. In Medienberichten ist die Rede von einer regelrechten Epidemie der Gewalt.

Seit der öffentlichen Diskussion dieser Missstände Mitte der 1990er-Jahre sei auf politischer Ebene nicht viel passiert, kritisieren die Betroffenen und ihr Umfeld. Eine groß angelegte, von der Regierung beauftragte Untersuchung mit dem Namen „National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls“, die von 2016–2019 durchgeführt wurde, sollte Aufklärung bringen. Sie kam zu dem Ergebnis, dass sich die Zahl der MMIW auf mehr als 4.000 beläuft. Eine genaue Ziffer ließe sich aber auch damit nicht ermitteln, räumt der Bericht ein, da viele der Verbrechen undokumentiert blieben. Es folgte eine öffentliche Entschuldigung des Premierministers Justin Trudeau. Zwei Jahre später wurde der „National Action Plan“ gestartet, 2022 gab es einen ersten Zwischenbericht. Gleich am Anfang dieses Berichts gibt es ein Kapitel mit der Überschrift: „Much Remains to be Done“, Zugeständnisse und Verfehlungen werden eingeräumt. Die Lage ist sehr komplex. Zu viel Zeit ist vergangen, zu wenig wurde bisher getan, sagen die Betroffenen. Sie fordern weiterhin konkrete Maßnahmen und Entschädigung. Die Proteste gehen weiter.

Die Residential Schools: verborgen, vermisst, vergessen

Heather Carroll verweist mit ihrem Kunstprojekt auf die MMIW, richtet sich in ihrer Kritik aber darüber hinaus insbesondere an die Praktiken der früheren Residential Schools und ihren Vorläufern in Kanada, die eine Brutstätte der Gewalt gegen Indigene Mädchen und Frauen darstellten. Die meisten dieser Schulen entstanden um 1880 (siehe weiter unten im Abschnitt zum „Indian Act“) und wurden bis 1996 von der kanadischen Regierung und christlichen Kirchen geführt. Gegründet wurden sie zum Zweck der Assimilierung Indigener Kinder und Ausrottung der Kultur Indigener Völker. Die Kinder durften ihre Sprache nicht sprechen, mussten sich gemäß der Vorgaben der Schule kleiden und verhalten, durften keinen Kontakt mehr zu ihren Eltern und ihrer Familie haben. Die Schulen waren stets unterfinanziert und überfüllt, die Kinder mussten häufig hungern, wurden teilweise gewaltsam der Obhut ihrer Familie entrissen. Unzählige erfuhren physische, emotionale oder sexuelle Gewalt. Und viele Kinder starben in den Schulen. In den letzten Jahren erfahren diese historischen Missstände auch hierzulande mediale und öffentliche Aufmerksamkeit, insbesondere nach einem grausamen Fund im Mai 2021, als auf dem Gelände einer früheren Residential School die Überreste von über 200 Indigenen Kindern gefunden wurden. Zur Aufklärung und Aufarbeitung dieses düsteren Vermächtnisses jahrhundertelanger Unterdrückung und Ausbeutung wurde 2008 eine „Truth and Reconciliation Commission“ einberufen, die die Geschichte und die Auswirkungen den Residential Schools über einen Zeitraum von 7 Jahren erfasste und dokumentierte. 2015 wurde der Abschlussbericht veröffentlicht, mit 94 Handlungsanweisungen für die Politik. Die von der TRC zusammengestellten und gesammelten Dokumente finden sich heute in der University of Manitoba.

Die systematische Benachteiligung Indigener Völker

All dies passierte vor dem Hintergrund jener eurozentristischen Vorstellung, mit der seit Jahrhunderten die Geschichte des neuzeitlichen Kolonialismus legitimiert wird: jener, gemäß derer die weißen europäischen Siedler:innen den Ureinwohner:innen überlegen sind. Das Aussehen, die Kleidung, die Bräuche, der Glauben, die Traditionen der Indigenen wurden damit als geringwertiger als jene der Weißen angesehen. Mit dem „Indian Act“ aus dem Jahr 1876 wurde diese Vorstellung schließlich rechtlich verankert und die systematische räumliche Zurückdrängung und Assimilierung der First-Nations-Bevölkerung institutionalisiert. Dieses Gesetz bestimmt den jeweiligen Status als Indigene Person, greift in das persönliche Leben der Menschen ein, beschneidet ihre Besitzrechte und ist allgemein stark diskriminierend, da mit ihm First-Nations-Geborene entmündigt werden und ihnen geringere Rechte zuerkannt werden als Weißen. In Folge dieses Gesetzes wurde es für Indigene Kinder verpflichtend, eine Residential School zu besuchen. Der „Indian Act“ hat immer noch starken Einfluss auf die rechtliche Situation der indigenen Bevölkerung Kanadas und auf ihre Lebensführung.

Die Verfassung von Kanada erkennt drei Gruppen Indigener Völker an.

First Nations: Ureinwohner:innen Kanadas unterschiedlicher Ethnien, die südlich der Inuit leben

Inuit: Indigene Völker der arktischen und subarktischen Regionen Nordamerikas

Métis: Nachfahren von First Nations und europäischen Siedlern, darunter vor allem Franzosen, aus der frühen Zeit der Kolonisierung Kanadas

Die Gruppen unterscheiden sich durch ihre Geschichte, ihre Sprachen, kulturelle Praktiken und Glaubensrichtungen. Bei der Volkszählung 2021 identifizierten sich 1.807.250 Menschen als Indigen und damit ca. 5 % der gesamten kanadischen Bevölkerung.

Interview: Heather Carroll und ihr Einsatz für die Indigenen Frauen

Mit diesen Hintergründen im Kopf können wir uns nun den Worten von Heather Carroll widmen. Die Künstlerin wurde als Tochter einer Inuit und eines Schotten in Labrador geboren. Sie ist eine Kablunangajuk, so werden Kanadier:innen genannt, die sowohl Inuit- als auch Nicht-Inuit-Wurzeln haben. Seit über 30 Jahren lebt sie in Luxemburg. Gemeinsam mit der Organisatorin Doris Eibl (Universität Innsbruck) sprachen wir über das Projekt, über das öffentliche Bewusstsein in Österreich und Kanada zu Kolonialismus und der Situation Indigener in Nordamerika und ihre jährlichen Besuche in Kanada, um ihre vielen Freund:innen „out West“ zu besuchen.

What is your project about? Can you tell me about “La Robe Rouge”?

Heather Carroll: This project came to light because of my becoming more and more aware of the situation of the residential schools that took place in Canada, which has taken a huge profile recently in the media. Everybody knew about it, but when the recent discoveries were made, it was like reliving the trauma for the people involved. For years I was thinking about how I could use my means as an artist to raise awareness about this situation and to increase or give indigenous people in Canada a stronger leverage on this subject to make it more internationally known. I learned about the red dress project early on, and one time I went to a fashion show where I saw a tipi dress worn by the granddaughter of the designer, who is my friend. So this has been gestating in my subconsciousness for the longest time. During Covid I suddenly I had the idea: I could make a big tipi dress and I could make it talk. So I bought a caravan that I could hook up to my car and travel around with the dress. The dress itself symbolizes women who have gone through abuse, as in domestic violence, the survivors of residential schools, but it also represents that we are still here. That is a catchphrase that is often used out West: We are still here. That is a sign of resilience. So this is actually the first exhibition that has taken place outside of Luxembourg. And I’m so thrilled to do it because it is giving this project greater credibility, greater exposure. It’s an ongoing project, I don’t know how it’s going to evolve. I am not a spokesperson; I am just a loudspeaker. People can come, make their contributions and ask for whatever help we can channel them. The focus is that the dress remains a safe place to be, a place where you can speak of your experiences, ask for help. We’re far from being any sort of professional structure, there are other associations out there that do that. But as it stands now for me this is a platform to raise awareness.

komplex: Where are you traveling next, are there any plans?

Heather Carroll: I’ll be in Vienna for the rest of the week, then I’m going back to Luxembourg. My ultimate goal is to take the dress to Canada. Next summer there will be intense fundraising and travelling, but I’m going to play it by ear. I’m just going to pack up the dress, get in my caravan and hit the road. I document everything that’s happening on this journey on my Facebook page “La Robe Rouge: hitting the Road”. I also use this page to spread other positive Indigenous news and repost what other people have done. Wherever I go, I take fundraisers with me – I make all kinds of little things and sell them. And I’m often surprised at the generosity and the knowledge of people. My pharmacist for example gave me a donation and said: I’m aware of the situation, I think it’s great that you do something about it. So, I hope that my friends out West can someday come with me on one of these caravan trips. In general, it’s all very organic, it evolves, it grows, it takes form depending on where it’s installed.

How did the cooperation with the University of Innsbruck happen?

Heather Caroll: I was working with the Canadian Embassy in Brussels. And one of the staff said he has given my contact to somebody at the Canadian Embassy in Austria. That was the last I’ve heard of it until a few months after …

Doris Eibl: I got a call from the Canadian Embassy in Vienna with a proposal to invite Heather Carroll. I liked this idea of an artist travelling around and setting up “La Robe Rouge” which has become emblematic for the red dress movement, as they call it. They even have an awareness day on May 5th now, which is crazy, I first heard about the MMIW in the mid-nineties when a professor from the University of Toronto, Barbara Godard, held a talk at the annual conference of the Canadian Studies Association in Germany. And she said: You can’t imagine what’s going on in Canada, indigenous women just disappearing, found murdered somewhere, dead, and nobody really reacts to that. And I was really struck by that. So when the proposal for a collaboration came, I really wanted to make it happen. We managed to get the necessary funding and I was thinking about where we could set the exhibition up when I walked past the newly built university building which now is Ágnes-Heller-Haus. Construction workers were still about, fixing things, and I asked if I could take a peek inside. When I saw the entrance and the foyer I immediately knew that this was the place. I contacted the new president of the University, Veronika Sexl, she agreed, and we fixed this very quickly. I’m happy that it all happened quickly because then other events were planned and the space wouldn’t have been available anymore. I think this is a perfect space for this because it’s a new building with new energy, and from an architectural perspective it’s interesting, with the staircases around it. My idea was also to make it public, accessible and visible, that people could just walk by, take a look and come near. There were a few people today that noticed us by chance, who sat inside the tipi, enjoyed the atmosphere and asked questions. Also we contacted schools – because I think that the University needs to connect with the outside world sometimes – and planned these beading workshops with the adolescent students as a means to educate students while creating something beautiful.

What was the idea behind offering beading workshops?

Heather Carroll: The beading as such is important to the Indigenous people. It’s not a very old tradition, it dates back to the 1800s. Beads were used as a trading commodity, and the First Nations people – as they often do – developed a huge capacity for working with them. So it’s become a part of their culture. When you bead, it’s considered a process which is healing and cleansing at the same time. I thought that doing a beading project with the young people would give them a sense of community, of working together, and it went really well. Everybody was involved and interested, they enjoyed themselves, in the end everybody left beaming. And that’s what these creative sessions are about, to create a community, to create a gathering, to create compassion, empathy.

What were some of the things that interested people the most or that you found most interesting about the exhibition and the workshops?

Heather Carroll: Globally today was a wonderful day whether it be the workshops with the classes or the people that approached us. When I saw that I had the attention of the students, that they were genuinely interested, that was a nice moment.

Doris Eibl: But what we also learned is that their knowledge background is so very different. You could tell that some had informed themselves beforehand about Indigenous people in Canada or residential schools, but not all of them. Being a specialist or Canadian studies scholar, I sometimes forget that people don’t even know about phenomena like the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. When you know a lot about something, you always think: Okay, this has been said so many times, why would I repeat it? But you have to start at zero. You need to tell them everything in order for them to understand.

Heather Carroll: That’s right: Don’t presume knowledge.

Doris Eibl: Exactly. Also, we are not in Canada here. This phenomenon is not part of people’s culture or their everyday lives here. They hear about it in the news and are affected by it for a couple of days, but then most of them forget. So if you tell people, you can’t take anything for granted. Because for the people who listen, it might be brand-new, it might be the first time they hear it. And that’s also you mission, Heather, in a way.

Heather Carroll: It’s a learning experience for me too. When I visit my friends in Canada, everybody knows. Here, nobody knows. I just returned from Canada, and I was talking about my project to my First Nations friends and asking people if they wanted to contribute, but there was only little input. I think there’s a certain fatigue going on. I respect that, because they have so many battles right now, from border crossing issues to everyday racism. This is just the surface, but, again: It’s all about explaining things.

Doris Eibl: It’s a complex situation, far more complex than we can imagine, in many ways.

komplex: Can you tell us something about your career background, your work as an artist in general. Where do you take inspiration from?

Heather Carroll: My studies were principally engraving, lithography, aqua tint. Then I worked as a graphic artist and illustrator. Relocating to Europe I discovered Luxembourgish Stone which I gathered because I found it so beautiful, and I put the stones in my studio. And one day I started to play with one and it turned into something. And the next thing I know I knew I was a sculptor. The stones basically define themselves; they tell me what they want to be and so I bring out that form. My work is often inspired by my dreams, but when it comes to the stone, the stone is the one that decides. I have a collection of stones, I have a small population in my basement, and I will take out one or two at the time and I look at them or they look at me and one day they will become something. I’ve got three in process right now, but next summer will be dedicated to the dress and the caravan tours. And as I was saying earlier to the young people: I’m so fortunate that I have done so well. And I think there’s always a giving back involved. And since I have this exposure, and with my background and so on I think it’s my responsibility to use my work as a vehicle to raise awareness about this. I’ve lived in Luxembourg for 33 years, but I go back to Canada every year because that’s what you do. But it’s highly unlikely I’ll ever go back to live there, because 33 years is a big chunk of my life and my friends are here, my network is here, I love Luxembourg, it’s a very beautiful country. Although I will be back to Innsbruck because it is such a wonderful place. Like I said I am in a position where I should use my skills as an artist that I have to raise awareness. So that’s what I’m trying to do.

Wer mehr über Indigene und von Indigenen in Kanada und ihr Leben, ihre Geschichten und Anliegen erfahren möchte: Hier kommen drei Buchtipps von Doris Eibl.

Michel Jean, Maikan. Der Wind spricht noch davon. Wieser Verlag 2022. (Roman)

Michel Jean wendet sich in seinem erstmals 2013 erschienenen Roman einer der finstersten Perioden der Geschichte Kanadas zu, die bis heute nicht wirklich aufgearbeitet ist: jene der Residential Schools.

Joséphine Bacon, Uiesh / Irgendwo. Gedichte. Klak Verlag 2021.

Joséphine Bacon lebt seit über 50 Jahre in der Québecer Metropole Montréal. Das Land ihrer Ahnen, Nutshimit, trägt sie immer noch in sich. Sie erinnert sich an Erzählungen der Ältesten, teilt ihr Wissen und erzählt von der Stille und Weite der Landschaft.

Sara Nickel/Amanda Fehr (eds.), In Good Relation. History, Gender, and Kinship in Indigenous Feminisms. University of Manitoba Press 2020.

Organized around the notion of “generations,” this collection brings into conversation new voices of Indigenous feminist theory, knowledge, and experience.

Quellen:

MMIW / Final Report

MMIW / National Action Plan

The Guardian / REDdress exhibit

The Guardian / Report on MMIW

Native Hope / MMIW

| Julia Zachenhofer