In her solo parsley for garnish, choreographer and dancer Sasha Portyannikova revisits one of the key figures of Russian dance modernism: Petrushka. The word Petrushka means „parsley“ in Russian, but it is also the name of a traditional puppet character that became well known in the early 20th century through the ballet Petrushka (1911) by Igor Stravinsky, Michel Fokine, and Alexandre Benois. It was produced for Ballets Russes – a ballet company that was established in 1909 by impresario Sergei Diaghilev in Paris. The ballet expressed the early 20th-century fascination with “Russian otherness,” framed through an Orientalist perspective that was en vogue in Western Europe at the time.

Sasha Portyannikova’s parsley for garnish developed during her residency at the Archive of Avant-Gardes in Dresden (ADA), as part of the joint program with HELLERAU – European Centre for the Arts. It is part of her ongoing research into forgotten or misunderstood parts of dance history. But it is also an exploration of her own background as post-Soviet artist.

parsley for garnish had its premiere in Innsbruck as part of OffTanz Tirol’s program „Laughing Gecko“ 2024. On November 20 and 21, it will be performed at the CPA 2025 in Salzburg. In our interview, Sasha Portyannikova explains the background of her piece and how colliding histories shape the way we see dance today.

This interview was created in collaboration with Choreographic Platform Austria (CPA)*

Your solo parsley for garnish emerged from your research in dance archives. Where does your interest for archives come from and how did it start?

Sasha Portyannikova: My interest in archives began during my master’s studies at Vaganova and intensified with the Soviet Gesture project (2017-2023). It was also at the core of the Touching/Moving Margins project that I co-curated (2020-2022). In 2023, I was in a residency at the Archive of Avant-Gardes in Dresden, and it was the first time I had been physically researching an archive – browsing through an immense amount of material. This archive used to be a private collection: Egidio Marzona had donated it to the city of Dresden. His archive is a conceptual project that also involves the idea of democratizing the archive, namely, not inscribing one object as more valuable than another. This influences the structure of this archive – not everything is catalogued in the same way as it is in institutional archives.

My interest in archival research began from a feeling that there are double standards in how dance history has been presented to us. I believe that working with my long-term collaborator Dasha Plokhova played a significant role in this interest, as she is a historian by first education (even before I met her in a dance master’s program). There is also a sense that something has been taken away from us. In today’s Russia, the government tries to claim the Soviet legacy, presenting it as a golden age. This causes many people, who disagree with the current government, to reject everything Soviet. However, some brave artists worked in Soviet times, and I don’t want to erase their legacy. It doesn’t belong to a dictatorship – it belongs to us as a cultural community. Those factors motivated Dasha and me to dive into Soviet dance archives and explore how artists can approach archival material through embodied practice.

Did you find something in the archive that surprised you?

Sasha Portyannikova: In the Archive of Avant-gardes, the biggest shock for me was the number of materials about Ballets Russes. When I requested the materials in Russian related to dance, I expected to find Soviet avant-garde works – because for me, as someone from a post-Soviet background, avant-garde is strongly linked to the Bolsheviks and Soviet culture. But in this archive, most of the materials were about Ballets Russes – a touring company led by impresario Diaghilev – which, for me, relates to ballet and the (post)-imperial aesthetics.

Of course, I am aware of the significance of their contribution to global culture: famous artists such as Michel Fokine, Anna Pavlova, George Balanchine, Vaslav Nijinsky, Bronislava Nijinska, and even Pablo Picasso, among others, worked with Ballets Russes. The choreographers and dancers were mainly from imperial Russian theatres, who immigrated after the Revolution. The company toured the world, producing works such as Swan Lake, Boléro, and The Rite of Spring; however, they never performed in Russia. For me, it was shocking that in this archive of the avant-garde, which I associated with the Soviets, I saw only imperial ballet.

How did you interpret that discovery?

Sasha Portyannikova: It was a total conflict in my mind.

Although the company’s aesthetic embraced European fascination with Orientalism and exoticism, it adapted Russian “otherness” to fit this orientalist allure. In this way, it made sense that they were in the Western archive – they did exist for Western audiences.

It also made sense, as after the Revolution, when the Bolsheviks came to power, many members of the Russian nobility fled to avoid persecution. So the Western image of the avant-garde dance was tied to émigré culture, while in Russia the avant-garde was connected to people like Vsevolod Meyerhold (1874–1940, avant-garde theatre director and theorist), Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948, filmmaker), or Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956, constructivist artist) – those who were radically breaking with the traditions and developing the new aesthetics that aligned, at least initially, with the new Soviet project.

This puzzle made me reflect on myself, being a migrant in Western Europe, and how people see me when I say I’m from Russia. When I tell someone in Europe that I work with Soviet dance archives, they imagine something completely different than what it actually is.

So would you say your research also revealed something about how the West frames Russian avant-garde?

Sasha Portyannikova: Absolutely. When I talked to Western dance historians or curators, they immediately brought up the Ballets Russes as something related to Russian avant-garde. That was very strange to me because in Russia, no one really talks about the Ballets Russes that way – it is rather Art Deco for us.

Now that I live in Western Europe, I sometimes feel myself in a similar position – outside, like those artists who couldn’t perform in Russia. That distance transforms how I see both myself and the history I’m researching.

You mentioned working with your colleague Dasha Plokhova. What was the aim of your common research?

Sasha Portyannikova: Dasha and I co-founded the dance cooperative Isadorino Gore in 2012 and, since then, have collaborated on numerous works together. We researched the archive of the Choreological Laboratory of the Academy of Artistic Sciences in Moscow, which existed in the early Soviet period. Wassily Kandinsky envisioned the Academy before he went to Bauhaus. The academy existed for seven years, and the idea was to research art with a positivist approach, as a natural science.

We didn’t want to contribute to the academic realm of knowledge, but rather to create something useful for our colleagues. Therefore, as a result of our research, we wrote a manual on how to work with dance archives – a practical guide for dancers. The project started in 2017; we published the manual in 2020, and later it became a base for the performance.

Through this work, we are questioning the widely held belief that contemporary dance in Russia began after perestroika [the political and cultural reforms of the mid-1980s in the Soviet Union, initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev]. All our teachers had been taught by people who came after the fall of the Wall – they were sharing what had happened in the West while we were behind the Iron Curtain. So, no wonder in our Master’s at Vaganova academy, we learned the canon of Western European and American dance. There were books on Soviet dance, but our teachers dismissed them, saying everything related to Soviet timeswas propaganda. Later, after graduation, we started to feel that there were double standards toward Western and domestic knowledge, and that’s why we decided to explore the Soviet archives ourselves.

How is your solo on Petrushka related to your research in archives?

Sasha Portyannikova: My research in the Soviet dance archive taught me that movement practice is the key to understanding any material. Whatever conflicting material I encounter, before relying on existing status-quo knowledge or jumping to any conclusions, I need to work with it through movement.

In the archive in Dresden, I found the photo negative of Petrushka. As an archival object, it had no description, meaning it was unclear what it was or who was in the photo. I was hypnotized by the fact that I recognized him immediately; however, Ballets Russes wasn’t my sphere of interest before. This is how I started to work on it, also to understand where that tacit knowledge comes from. There’s no video documentation, only reenactments. I studied them and found it interesting to see which gestures stayed the same and which changed. It made me think about what we capture as the embodied “essence” and how a character travels through time.

The ballet was staged by Russian nobility, who often spoke French among themselves and were closer to European-educated society than to the folk culture they were representing. It was a kind of simulacrum – an imitation of something they didn’t fully live. My image of avant-garde dance is formed by the aesthetics of Meyerhold’s biomechanics, the plasticity of Soviet monuments – geometrical postures of workers and soldiers. Petrushka’s gestures, his rigid glove shapes, surprisingly align with those shapes.

For me, Petrushka is a character where worlds collide. The ballet was created before the Revolution, when everything was about to collapse. Through this solo, I realized that what we perceive as “avant-garde” sometimes depends entirely on where we stand.

In the solo, do you perform as Petrushka or as yourself?

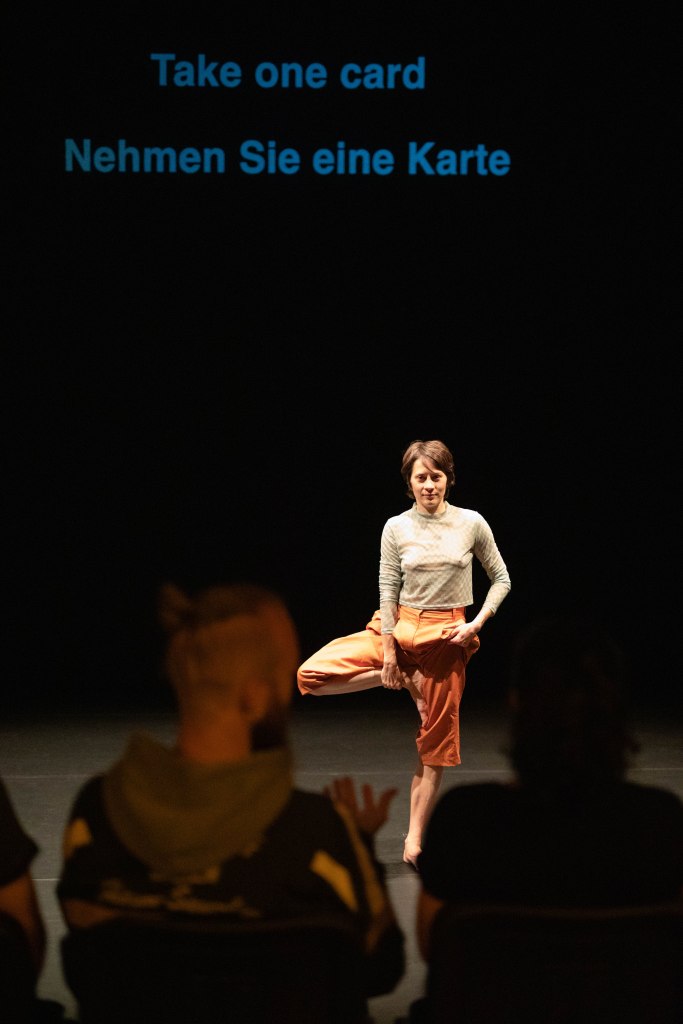

Sasha Portyannikova: In the performance I am myself. The solo is autobiographical – I talk about going to the archive in Dresden and encountering all these contradictions. There’s also an interactive element: a card game that invites the audience to move around the room and change their perspective. The score combines romantic and avant-garde movement ideas. Petrushka appears briefly, but then disappears – I return to myself.

And your colleague Dasha Plokhova – do you continue to collaborate?

Sasha Portyannikova: Yes, we keep working together, but not in this solo. Since I emigrated, we have explored digital tools that allow us to keep working. We made the piece Handcrafted Digital Morphing and Soviet Gesture, which is also participatory. We invite the audience to recall and deconstruct memories of Soviet-era movement. We performed it remotely – I was in my apartment in Innsbruck, and Dasha was in various venues of Moscow and Yekaterinburg. And we are working on the new piece right now – exploring how contemporary media affects human perception and relations.

I deeply respect my colleagues who remain in Russia. They teach children who would otherwise only be exposed to propaganda. It’s important that some people stay and keep other perspectives alive.

| Brigitte Egger

*CHOREOGRAPHIC PLATFORM AUSTRIA

Die Choreographic Platform Austria (CPA) verfolgt das Ziel, das vielfältige choreographische Geschehen in den österreichischen Bundesländern sowohl für ein überregionales tanzinteressiertes Publikum als auch für internationale Expert*innen sichtbar zu machen. Dies wird einerseits durch eine biennale Veranstaltung erreicht, die ausgesuchte Tanz- und Performanceproduktionen aus Österreich präsentiert. Andererseits fungiert die CPA als Onlineplattform. Diese dient nicht nur dazu, Institutionen, Initiativen und Künstler*innen aus Österreich zu porträtieren, sondern auch als kuratierter Eventkalender, der einen Überblick über das Choreographie- und Tanzgeschehen in den einzelnen Bundesländern bietet.

Sasha Portyannikova

a dance artist born in the Soviet Union, raised in Moscow, lived and worked in Berlin and New York, and is now based in Innsbruck. A graduate of the Vaganova Ballet Academy (M.A., 2013), she co-founded Isadorino Gore with Dasha Plokhova in 2012, became a Fulbright Visiting Scholar in 2018, and has co-curated Touching Margins since 2020. Her work explores diverse dance heritages and the complex interplay of cultures and politics.