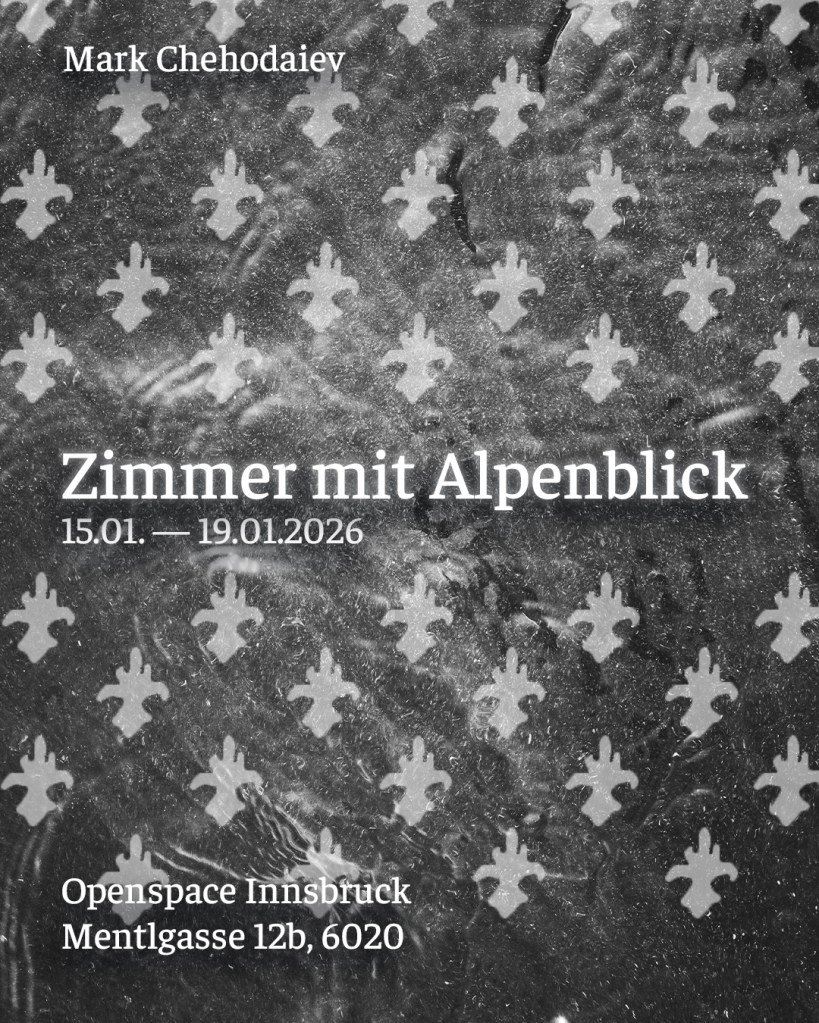

A curator’s note to the exhibition Zimmer mit Alpenblick (Mark Chehodaiev)

by Anastasiia Diachenko

Growing up in a Ukrainian family with above-average income, children often have/had the opportunity to travel abroad at least once a year. I had this privilege twice. Winter trips, usually at the beginning of snowy February, always had one destination — Tyrol. I still remember the slight twinge in my stomach when the train that picked us up from the airport rushed from Munich to the Alps, almost imperceptibly disconnecting somewhere before Innsbruck and taking me and my parents to one of the tourist mountain villages. Checking into a hotel, which usually had at least three stars, was almost ritualistic. The first step into the room meant a new beginning — a perfectly clean slate on which to neatly lay out your best things. Later, they would appear at breakfasts, dinners, and on snowy slopes. Sometimes it seemed that even in your own room there was a subtle but recognizable smell of the spa area — warm, humid, with hints of pine. The corridors were filled with people wearing expensive rings, fur coats, and a perfume of luxury in their temporary presence. Staying in this almost utopian capsule gave a feeling of freedom. Far from everyday worries, “unburdened” by anything but snow-white bedspreads and tablecloths.

Times have changed. COVID, four years after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and the large number of hotels we saw while traveling around Tyrol in search of the best ski slopes, have lost their original function and turned into social housing for temporarily displaced persons and refugees from all over the world, but mostly for Ukrainians. Since 2023, multidisciplinary artist Mark Chegodaiev has been exploring these spaces in his project Hotel Europa. Since the fall of 2024, I have been fortunate to collaborate with him on this research, and in September 2025, together with filmmaker Dmytro Churikov, the three of us visited several such hotels.

The first thing that catches the eye is the empty but still perfectly laid tablecloths on the large dining tables. The soft armchairs are too far apart, and the chandeliers illuminate the emptiness. The common rooms, which seem to be still waiting for noisy guests and social conversations, are now inhabited in a slightly different way. The current residents pass through them almost imperceptibly, like shadows, heading to the kitchen or back to their rooms. They are not temporary visitors — rather, the most permanent of all who have ever stayed here. This ghostly loneliness is most strongly felt near the pools. Empty pools, closed spa doors, signs with rules, along with junk that doesn’t belong in this space. Now they are sealed containers in which silence is concentrated.

I’m watching Mark. He’s looking around carefully, without excitement, but focused, as if he’s putting together a timeline of events. Who put this cart here? How many people sit at this table every day? Were these flowers in the garden planted by former employees or current residents? His gaze does not focus on aesthetics — it focuses on traces.

We take the stairs to the third floor. This is the part that fascinates me the most. People open the doors to their rooms. At first, very cautiously, with distrust. This acquaintance takes place on the border between curiosity and fear. Mark begins to speak — usually very simply, asking how things are going. He does not insist, does not ask unnecessary questions, he leaves space. I am struck by how quickly trust arises. How, at a certain, completely sudden moment, the main thing becomes clear — why these people want their rooms to be photographed. Why do they want to be in the photo themselves.

These rooms are overflowing with everyday objects that are unnatural for them. What is usually located within the confines of an apartment has to fit into fifteen square meters here. The space is forever changed. There are attempts of comfort — decorations, personal items brought from home. Sometimes small gardens with tomatoes or dill appear on the balconies. Some people bring their work practices here — repair stations, sewing machines, easels, sports equipment, or giant computers.

For the average consumer, a hotel often symbolizes a pause — a carefully designed temporary space where everything works to erase the traces of everyday life. Here, this temporariness stretches out, loses its contours, and becomes a form of existence. It is this transformation that Mark captures on film. He is not interested in the event itself, but in the space after the event. Not the person as an image, but their environment, which changes along with them. Here, hotels act as architectural bodies that have lost their original function but have by no means lost their memory. In this memory, spaces are filled with movement, noise, and the expectation of first-class service. Mark, however, sees them in a state of pause, almost at a standstill. He sees their loneliness.

In one of the hotels, we noticed an inscription on the wall — „der Zug hat keine Bremsen“ (The train has no brakes). We never managed to find out who left it there and when. I think this phrase refers to a state of movement without the possibility of stopping, a life in inertia. The hotel no longer promises you freedom or escape — it becomes a quiet isolation. Its architecture, designed for short pauses, is forced to adapt to a constant, cyclopean presence, offering its residents no tools for the future. Here, presence ceases to be a choice, rather, it becomes a fact that one has to coexist with every day, without the possibility of distance.

| Anastasiia Diachenko

The exhibition opens on Thu, Jan 15th at 18pm at Openspace Innsbruck.

Opening Hours:

16.01 + 19.01. 15 -16pm

17.01 + 18.01. 14-15pm