At the beginning of this year (January 15-19th 2024) Kunstraum Innsbruck hosted Jelena Vesić, theorist and curator, to hold the course Solidarity in Time on the historical Non-Aligned Movement and its impacts on the world of contemporary art. The course was organized by curator Ivana Marjanović in collaboration with the Institute of Philosophy. It was open for PhD students attending the course “Dynamics of Inequality and Difference in the Era of Globalization“ at the University of Innsbruck, but also open and free of charge to the public. We also followed this invitation and provide here for you some insights into the topics of the program, contemporary references (Museum of African Art Belgrade, Ljubjana Biennale of Graphic Arts), as well as an in-depth-interview with Jelena Vesić.

The course Solidarity in Time dealt with the impact and traces of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), its relevance for the world of contemporary art and its role for global discourses on decolonialization. The NAM originated in the mid-20th century during the Cold War. It was a vision by countries who didn’t see themselves aligned with either the Western or Eastern superpowers, claiming their state of autonomy amid the two major ideological fronts. Rooting in the Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung (Indonesia) 1955, the Non-Aligned Movement was finally established in 1961, at a summit in Belgrade, and by that time, it marked one of the greatest anti-colonial movements on a global scale. Its major political leaders and founding figures – Josip Broz Tito (Yugoslavia), Jawaharlal Nehru (India), Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt), Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Sukarno (Indonesia) – were not only advocating for self-determination and an independent stance in global politics, but with their political aims, they also played a crucial role for the global discourse on anti-imperialism and decolonialization. With the NAM, a platform and voice of the “global south” was implemented that has been shaping topics and networks in politics, in society and in the field of contemporary art until today.

Even if Austria was not politically involved in the Non-Aligned Movement, curator Ivana Marjanović emphasizes the relevance of educating the visitors to Kunstraum Innsbruck about this historical resistance movement:

“The Non-Aligned Movement was very important not only for former colonies but also for Europe and the world because it represented an alternative to the binary division of powers. The fact that Yugoslavia was involved breaks the monolithic image of Europe as nothing other than colonial and imperial center. Europe was (and has been) that, but it was also a place of anti-capitalist, anti-fascist and anti-colonial struggles. Through Yugoslavia’s participation in the Non-Aligned Movement, this movement was not somewhere out there, far away on another continent, but very close (in the case of Austria, it was a neighboring country). And these resisting movements to totalitarian communism and capitalism even took place at the highest diplomatic level”.

– Ivana Marjanović

Nevertheless, the history of the NAM is not widely known in our society. And even in the countries of the former Yugoslavia, it is increasingly being forgotten. “I think it is crucial to understand how and why different historical solidarities emerged and how they got thrown into the dustbin of history. The more we try to understand the continuous and discontinuous dynamics of inequalities, the easier it will be for future generations to find peace”, says Shaghayegh Bandpey who participated in the course. As a member of the doctoral college Dynamics of Inequality and Difference in the Age of Globalization, she is currently doing her PhD in Philosophy at the University of Innsbruck with a focus on political economy and aesthetics. Bandpey recently wrote a philosophical paper in which she attempted to analyze Richard Rorty’s duality of solidarity and objectivity in relation to contemporary discourses and world events.

“Therefore, it seemed important to me to take this course. It is vital to understand the world’s current solidarities, as well as those that are slowly disappearing – and the reasons for this.”

– Shaghayegh Bandpey

During the course Solidarity in Time, the intertwinement of politics, histories and aesthetics became evident. Through text readings, in-depth artwork analyses and online-discussions with invited experts, Jelena Vesić presented various narratives of resistance and examples of solidarity inspired by the ethos of the NAM.

The Anti-Colonial Museum – an Oxymoron?

One of the invited experts via Zoom was Ana Sladojević, theorist and former curator at the Museum of African Art (MAA) in Belgrade. Established in 1977, the MAA was a manifestation of the NAM’s emphasis on fostering cultural exchange, dialogue and solidarity among the non-aligned nations. It was initiated by two Yugoslavian diplomats, Veda Zagorac and Zdravko Pečar, that founded the museum based on their own collection of objects. During their visits to African countries, these artefacts were either gifted to them or purchased. The fact that the exhibited objects in the MAA were not appropriated (as most of them were in western African museums), led to the museum’s claim as being “decolonial” or “anti-colonial”.

“However, no museum is anticolonial per se”, says Ana Sladojević, who presented her own curatorial research project titled An Anticolonial Museum at the MAA. “If we observe the history of museums as such, we can see it is tightly interwoven with imperial and colonial discourses and contexts. This entwinement is visible in the ways museums were established, organized, systematized”. As the way, in which the MAA operates as institution, doesn’t differ from other (colonial) museums, it fails its anticolonial idea. If it cannot serve as “anticolonial”, at least it serves as institution for critical thinking and knowledge production. With her work, Sladojević took a self-critical approach in reflecting the museum’s position.

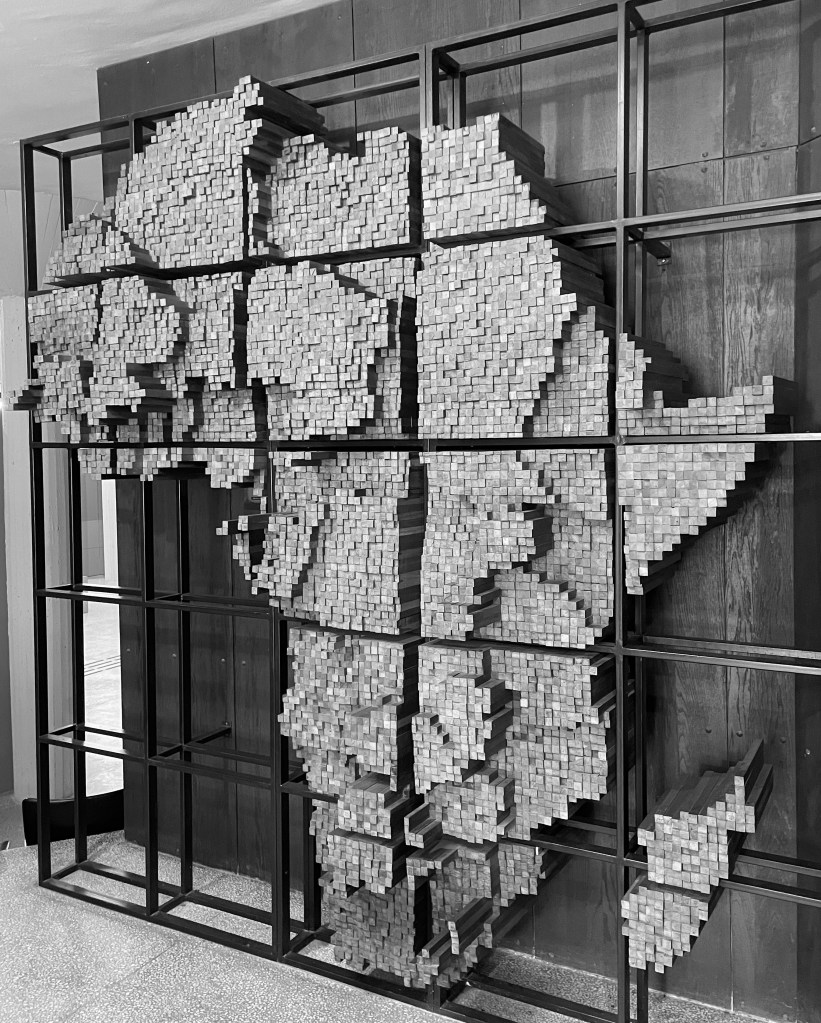

Despite these definition-related problematics, the MAA played an important role in the process of decolonialization and in the friendly and respectful political relationship between Yugoslavia and African countries. When entering the museum, a three-dimensional shaped sculptural map of Africa is the first thing noticed by visitors. It was created by the artist Nikola Kolja Milunović and offers alternative perspectives on African countries besides western-centric cartographies. One of its most interesting aspects, as current curator Ana Knežević points out, is the fact, that borders of certain African countries, which hadn’t yet gained independence by that time, were visualized in the map. For example, borders of Namibia were already acknowledged by the museum in 1977, although Namibia was officially declared independent not before 1990.

After the Yugoslav wars and the breakup of the state in the early 90s, the Socialist Federal Republic was disintegrated by the NAM as it weakened its coherence and unity. Consequently, its values became more and more forgotten, which has also changed the role and status of the Museum of African Art in the region. Today, the museum continues as a ruin of its own history, the history of the NAM.

“The best way to develope this place, I believe, is to keep its history and meaning visible all the time, but also to update the critique, understanding, and thinking of the same history in relation to the contemporary moment“,

points Ana Knežević out. As curator, she emphasizes the museum’s role in educating the public on the history of the Non-Aligned Movement, not only for the sake of its memory, but also because it serves the future: “Through research and education on the values of the Non-Aligned-Movement, we can think alternatives to current political circumstances”, says Knežević, “and the educative role is relevant, because this part of history became rather forgotten or marginalized in our society. It is not anymore an important subject in schools”.

Echoes of Solidarity – the Contemporary in Yugoslav’s Aftermath

Parallel to Jelena Vesic’ course in Innsbruck, the 35th Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts held its closing events. Since its establishment in 1955, the Biennale has become an institution in the contemporary world of art, following the ethos of the Non-Aligned and the Yugoslav policy of “active peaceful coexistence”. In its early editions, it served as platform to showcase works beyond Western and Eastern hegemonial structures and war ideologies. It has also been functioning as a platform for building connections and fostering dialogue across borders and cultures.

After the Yugoslav wars the role and circumstances of the NAM have shifted in the region, but the Ljubjana Biennale continues to embody its values and keeps its spirit alive. The 35th edition, titled From the void came gifts of the cosmos, explored the ecosystem of friendships, solidarities and histories of resistance between post-independence Ghana and the former Yugoslavia, as the editorial team emphasizes in their biennale reader: “The void, as it is intended in this context, functions as a necessary correlate of universality, which is to say the cosmos. It operates as a space that necessarily privileges no centre”. The Biennale was curated by the artist Ibrahim Mahama and his collaborators: Exit Frame Collective, Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh, Alicia Knock, Selom Koffi Kudjie, Inga Lāce, Beya Othmani and Patrick Nii Okanta. “I was interested in what the void means [or could mean] in terms of egalitarian politics for our century“, curator Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh comments, “and this is relevant because the imperialism still endures in different forms until today. And since the empire always assumes its horizons of freedom or inclusion from the few who have power and can exercise it, there is a need to return to ideas that begin not at the center but with the exceptions”.

In a series of events, the curatorial team presented works of contemporary art and printmaking and hosted workshops which reflected on the emancipatory visions of Ghana’s first president Kwame Nkrumah and the lasting cross-border-network of the NAM. They presented artistic positions, which reflect on urgent issues faced by societies worldwide, such as questions of identity, social and climate justice, hegemonic ideologies, and legacies of colonialism. “For me, the true potential of this Biennale was to test the form of universality in aesthetic terms to see what it would bring”, says Ohene-Ayeh, “this also influenced the selection of artists and collaborators who contributed to the biennale”. One of them was the artistic-research-collective Nonument Group (they were also performing at Kunstraum Innsbruck last year) from Ljubjana, which presented an archive of the Pioneer Railway. In their performative soundwalk project, they were dealing with the topic of erasing history and made socialist values of community and labour visible to their audience.

“As the Void is a space that can accommodate consensus, contradictions, tensions, binaries, paradoxes, ironies, etc., it seemed to offer us a compelling framework in which to carry out a variety of artists‘ interventions. By offering tools, histories, axioms and ethics with which a truly egalitarian politics could be explored, the void serves as a cipher that has the potential to bring power back into the space of the multiple, rather than being trapped in the hegemony of binarisms.“

– Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh

The two given examples show the current impact of the Non-Aligned Movement after 50 years of its existence. They also remind us that artistic expression can be a powerful tool for change by advocating for a world that embraces diversity and rejects neocolonial forces.

Although, meanwhile the NAM has lost its power as global revolutionary political movement, it continues to influence the global world of contemporary art and even society in terms of bringing people from different cultures together and encouraging dialogue. Therefore, when learning about the NAM as part of history, we can draw inspiration from its principles for thinking a better future – for global equality, respect, and solidarity.

In conversation with Jelena Vesić

komplex: As independent curator and researcher born in Yugoslavia, why did you personally decide for the Non-Aligned Movement as one of your focuses?

Jelena Vesić: I’ve been dealing with the socialist solidarities and politics of art in the context of Yugoslavia, Eastern Europe and Global South for more than 15 years. I’m interested in (art) historical frameworks and narratives and how they are made in the specific social-political constellations. My path to the histories of non-aligned was rather organic, situated in my interest in emancipatory histories and the post-socialist ideological context. I was part of the independent scene in Belgrade that came into being after the wars of the 1990s, confronting the national state institutions of the newly consolidated national cultures of former Yugoslav republics.

In 2009, I curated the collective exhibition project Political Practices of (post-) Yugoslav Art in the Museum of Yugoslavia, which gathered many interesting people from art and theory, curatorial and artistic collectives who critically examined the hegemonic representations of Yugoslav art together with the narratives on regional art histories that still dominate the field of museology of global mega-museums. This was the beginning of my interest in epistemic decolonization and “unmaking” the art-historical narratives.

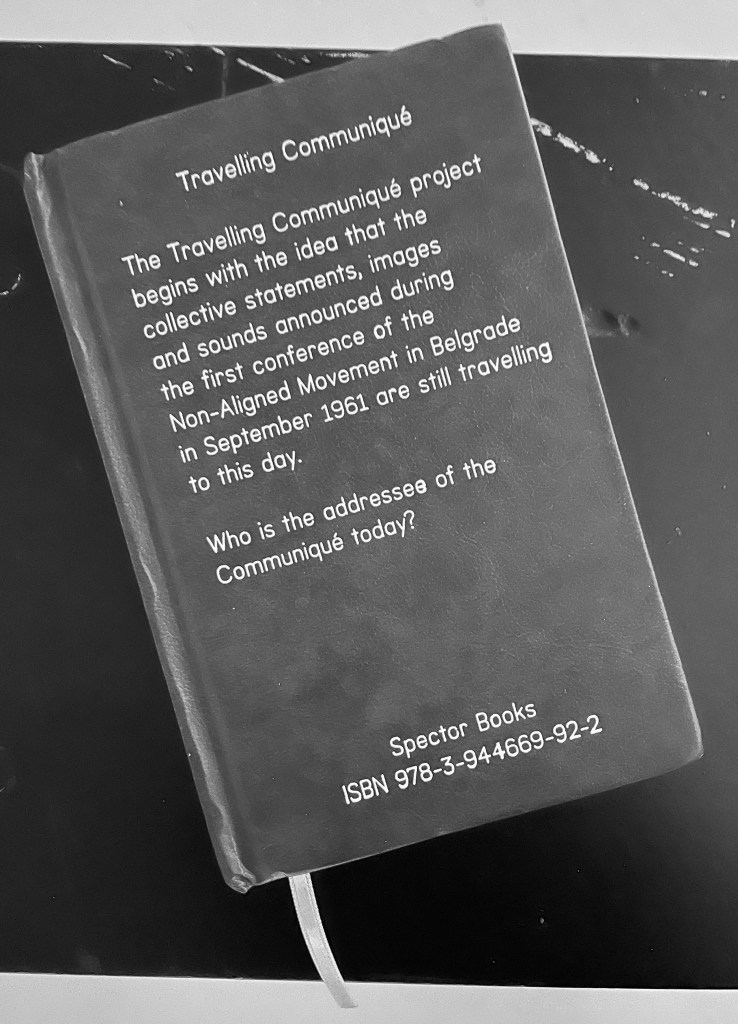

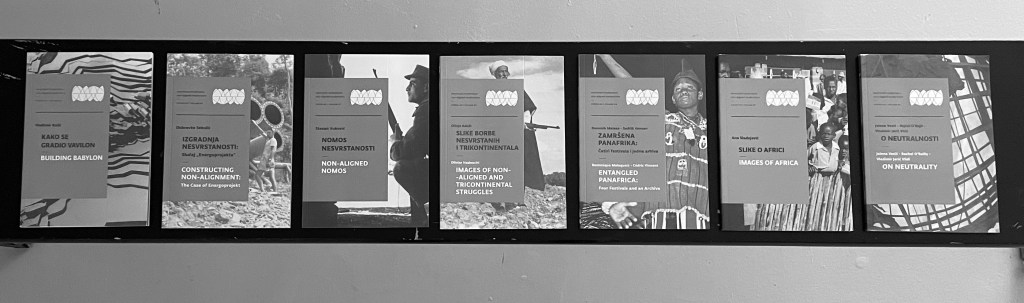

Shortly after the exhibition and the publication of Political Practice of (post-) Yugoslav Art, I entered new collective researches on the legacy of the NAM such as the publishing project Non-Aligned Modernism and the exhibition-research Travelling Communique initiated by Doreen Mende, Armin Linke and Milica Tomić.

Could you tell us something about your course at Kunstraum Innsbruck? How do you frame the discussion about the Non-Aligned Movement and the concepts of Third World and Global South in your research?

The course “Solidarity in time: The images of history and Contemporary Art” delves into art and intellectual production that thematizes theories and practices of decoloniality and the processes of unlearning the cultural-political narratives based on white supremacist modernisation.

The concept of solidarity in time approaches politics as a processual and continuous struggle that entangles past, present and future. It engages with the questions of how to think the present historically, how to understand non-linearity of historical time and not-nowness of the present time. How contemporary artists, theorists and exhibition makers, think about emancipatory struggles of the past in the present moment and how this knowledge can be actualised in contemporary thought and action.

Non-Aligned Movement’s intervention into power politics of the two Blocks, is considered from affirmative and critical perspectives. The politics of Non-Aligned was nominally and declaratively opposing the systems of domination and oppression, offering an alternative form of worldism to contemporary capitalist globalisation. But, in practice, the NAM was also race-blind and permeable for internal racisms and oppressions happening within the very member states of the Movement.The Non-Aligned Movement was symbolic for the era of decolonization and gaining of national and cultural independence of the newly liberated nations in Africa, Asia, Latin America. “Third World” for Vijay Prashad (author of The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World, 2008) is not a geographical concept, but rather a cultural-political project, which he “triangulates” in global historical time-space through the events of Afro-Asian Conference (Bandung, 1955), Non-Aligned Movement (Belgrade, 1961) and Tricontinental conference (Havana, 1966). This was one of the grounding points of my course, in which the iconic images of Non-Aligned Movement were observed in comparison with Bandung and Tricontinental. The filmmaker and writer Olivier Haduschi who wrote about the images of liberation wars as the images of solidarity (in his book Images of Non-Aligned and Tricontinental Struggle, 2015) reminds us that the very concept of Third World referred to the Third Estate: “They strove to take destiny into their own hands and to do everything to make their voices heard”.

In your talk for the Sharja Art Foundation conference “Revisiting Global 60s, March Meeting 2023”, you are mentioning the “Angel of history” which is looking at the past, acting in present and contemplating the future. It reminded me on Walter Benjamin’s conception of the dialectical image and his references to Paul Klee’s “Angelus Novus”. How do you read the “images” of history?

I understand history as a “sphere of struggle” – close to Benjamin’s concept of “historicity as actualization”. My aims are primarily (self-)educational, in the sense of setting up models for independent research into lesser known histories that could give us a different perspective for positioning and acting within the framework of today’s situation. This is not to be simplified to the statement that we can directly learn from history such as in Cicero’s claim that “Historia est Magistra Vitae“. No – we can not learn from history, but learning history and historical thinking can help us in contemplating alternative futures.

The concept of solidarity in time starts from the assumption that the images of history in contemporary art, theory and political practice represent a relevant field of struggle, regardless of the technological-media and psycho-experiential insistence on the present or the social reproduction of supernow.

The return to the historical past, which is the subject of numerous works today, often meets with a double dead end – on the one hand, the problem of apologetics of the past, heroic-nostalgic images of a “better yesterday” (reflected in the writings of S. Boym, B. Groys etc); on the other hand, the problem of reactionary historical revisionisms and overproduction of post-historical fictions (reconstructive spectacles) unfolding hand-in-hand with the strengthening of the populist right in the world after 1989. Today, it often looks that the struggle is not performed in the name of the present but in the name the past. The use of historical image is therefore very delicate.

As Ana Sladojević was pointing out via Zoom in your course, there wouldn’t exist such thing as “anti-colonial museum”. What do you think about the discourse on decolonialization in contemporary art – referring to your thesis on stealing from history and the political economy of an archival image?

An image of long duration and long struggle is, at the same time, an image that may enter excessive use and consumption, an image whose political meaning fades or becomes the very space of the struggle ‘for’ the image and ‘by-the-means-of’ the image. The themes of history, and specifically the emancipatory moments of Yugoslav socialism, in the meantime became the basis of artistic identities in the post-Yugoslav region and a kind of trend, I would say – a genre, in which history and politics are appropriated for the success of the individual authors on the critical art market.

In the photograph and artistic action by Milica Tomić Purloined Letter (Edgar Allan Poe), from the year 2014, the artist walks down the Museum of the History of Yugoslavia’s steps, carrying a zoomed-in fragment of the famous photo of the Non-Aligned leaders – a sort of an ‘official photo’ of the Non-Aligned Movement and its establishment during the Belgrade Summit in 1961. The artist snatched away this fragment, almost stealing it, using the photographic reproduction of the performance to precisely symbolize the fragmentation of common history under the banner of artistic authorship. The artist’s body is hidden behind the painting, completely covered by the painting; It is only a support, an engine, a mobilizer, as if the painting itself is running away through the forest, or as they say about a stolen object, ‘it got legs’, which is literally presented in this work. The stairs are surrounded by a deep forest and seem to lead nowhere, and towards something we can’t see yet.

Purloined Letter – that I read as a symbol of political economy of an archival image in contemporary art – reflects on the constellations of history and property in the age of expansion of historical revisionisms and politics-without-truth. The renewed archival fever within contemporary art often renders a sentimental fetishization of historical facts and images, without true historical responsibility. The practice of relentless appropriation, packaging, and repackaging of common heritage is branded as artistic research and signed by artistic name as private property.

So, thinking of Milica Tomić’s photographic action/performance, I am posing the questions: Who profits from history, archives, and historical legacy, and who undertakes the politics of historicization responsibly? Who has the right to these images? What is the ethics/politics of the artistic appropriation of historical content? How to do history in a common space, without fencing off a territory and putting up a board with the author’s name on private property?

The course was titled after your concept of solidarity in time. What does solidarity mean in this context – what is its relation to time? How do you see solidarity manifesting in the art world?

The concept of solidarity in time stems from the concrete essay that I’ve written for the project-book Past Disquite by R. Salti and K.Khouri where I developed it for the first time interconnecting my art-historical inquiry and the contemporary action of the artist Darinka Pop-Mitić, with the muralists of Salvador Allende Brigade and The week of Latin America in Belgrade in 1978. Using the concept of solidarity in time I put an accent on contradictions, on the processes of collaging and de-collaging historical moments and images in sharp cuts, on building the meaning of artistic-political gesture that does not ally with both: the art-historical/museal epistemic canon of reginal paradigms (regional art histories) or the academicized canon of artistic research spiced by political archival images.

To be contemporary (con-, tempora-)means to live with time and in time, to live within one’s present; but it also assumes certain solidarity in time, sharing the particular moments of time with both the past and the future. Living in the present moment, in which the promise of historical progress and a better future waned, we are provided with an illusion that we live in the era of an absolute chrono-democracy, in which all the historical moments seem reachable and easily accessible, ready to be performed, experienced and consumed. Our memories are simulated and assembled from various pasts that are spectacularly presented in reality-show-like digests on dedicated History ChannelsTM. Everything, including the World Wars, now runs again – and “this time, in colour.”

I am using the term politics of historicization, which for me, in the contemporary context assumes a certain struggle, a struggle in time and with time, but also a struggle for a politic that deserves the future – and therefore deserves “to be included” in the past, to be remembered historically.

You published the book “On Neutrality” in the frame of the series Nesvrstani Modernizmi /Non-Aligned Modernisms (the series was a pioneering project of the research of NAM that included many case studies from architecture to moving image and the politics of war and peace). In current times of wars, crisis and conflicts, does it make sense to you to keep a position of neutrality rather than choosing sides?

Neutrality as a political concept has existed as long as there has been warfare. At its simplest, neutrality means not taking part in a war, or, in more durational terms, to remain uncontaminated by great rivalries. But with any second glance through its conflicting legacies, the terminological negativity of the Neutral gets quite complex, as it continues to be utilized across progressive and conservative, legal-normative and revolutionary identifications. In the political wording of the Non-Aligned Movement active neutrality or politicised neutrality became synonymous with independent politics, (national) sovereignty, respect for (inter-national) sovereignty, politics of “eternal peace”, solidarity, friendship and equality.

Kwame Nkrumah wrote “This politics of non-alignment and de-linking certainly does not have to be interpreted as if my government decided to play the role of silent observer of world issues, or the issues that are concerning the interests of our country and the destiny of African people. Our politics of positive neutrality is not passive or neutral politics — this is affirmative politics based on our firm belief into positive action.” The negation of power politics, symbolically captured by the historic Bandung Afro-Asian conference of 1955, marked the movement of the bipolar Cold War condition towards an officially novelsituation. The emerging forces of new and socialist nations articulated the project of political peace — as a form of collective solidarity. Their proposition was a claim of decisionist power within, but also beyond the design of the UN Charter’s post-war project.

I worked on the book with the feminist artist and theorist Rachel O’Reilly and mediologist Vladimir Jeric Vlidi. Within the history of Non-Aligned Movement, we located Neutrality not as a static term, nor a petrified legal institution, but rather a dynamic category of position taking. Our research experiment tracks through Neutrality as a political discourse of comportment, as a strategy, and as a historic geopolitical phenomenon, constitutive of philosophies of war and peace, or of inequality in conflict.

In Marx’s classical works, the wars of the bourgeoisie are always inspired by goals of conquest, which lead to the enslavement of other nations; by this fact, these wars (i.e. vast majority of wars) are unjust wars. In Marx and Engels, we find a movement beyond the thought of war as the conflict of two sides towards a larger comprehension of revolution worked through the extreme experience of war’s hardship on both sides, whereby the proletariat splits from imperial identifications to take up socialist revolutionary investment. In Lenin’s writings on the military program of proletarian revolution, just wars are seen as a continuation of the politics of struggle against national oppression, or as the struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie – such wars Lenin considered inevitable and revolutionary.

I am juxtaposing the notion of active neutrality to contemporary neutralization of politics in the conflict management – the so-called normalization as the constitutive element of the permanent war. Giorgio Agamben evokes the greek term stasis, which means both civil war and immutability, a civil war that is unresolved and drags on. Conflicts today do not lead towards a resolution of a disputed situation, but serve to a stagnant crisis, and the crisis is – as it is painfully clear – an abundant source of profit.

How do you consider the role of (contemporary) art for the NAM which was mainly a political movement?

Contemporary art and autonomous artistic research of the micro-histories of the NAM, reveal alternative and affirmative models of independent action in the global racialized capitalism, in the times of its acceleration and excess. A number of theoretical-artistic projects dealing with history are precisely addressing epistemological decolonization and anti-racism. Many projects refer to the histories of Non-Aligned Movement only by using the word non-alignment itself, by relying on its political semantics, without researching and presenting any specific historical moment of NAM. The signifier of non-aligned in such projects is used to mark their ethics and politics within art and knowledge production, their dedication to subjugated or difficult knowledge; their insisting on different human and economic relations compared to the hegemonic formats of the global institution of art, whose real interest is success and power (author’s brand).

I also make a distinction between art historical reconstructions and contemporary art projections. Historically and real-politically the non-aligned movement and its cultural representations and exchanges had the purpose of propagating national liberations by images and cultural propaganda. The cultural cooperation, cultural politics and networks of the Non-Aligned Movement were mostly inter-state projects. Examples of autonomous artistic activity are very rare. Exhibitions, art exchanges, cultural and educational projects and collaborations were usually financed either by international organizations (UNESCO) or by the state itself for propaganda purposes.

Contemporary art, in comparison with historical research-reconstructions and detailed anamnesis of facts, however, introduces a position that is imaginary, it does not repeat the historical gesture itself, but adds something to it, a different register of speech, a different atmosphere and affect. The images of history of the Non-Aligned Movement in contemporary art acquire an imaginary dimension (they are not images of reconstruction and repetition, but of imagination and projection). The very political gesture of refusing to align with the ruling paradigms of globalization and racialized capitalism and relying on one’s own strengths instead (one of the mottos of the politics of non-alignment) becomes a kind of projection, projective politics in relation to the ruling paradigms of globalization.

As a conclusion – what is your suggestion on how the topic of the Non-Aligned Movement should be approached, when thematizing it as a part of history?

Of course, whenever we speak about the past, the issue of nostalgia comes up, the return to „better past“, to „good old times“ – the phenomenon that Svetlana Boym precisely described as “history without guilt.” Many contemporary projects dealing with history are falling into that trap of being apologetic and melancholic about an idealised image of the better past. I think we should be open to the critique of all existant and reflect the failures and unfulfilled promisses of the emancipatory histories. In my approach to Yugoslav self-management socialism and the Non-Aligned, I insist on a differentiated, critical and non-nostalgic attitude.

| Brigitte Egger

Jelena Vesić (PhD)

is an independent curator, writer, editor and lecturer. She is active in the field of publishing, research and exhibition practice that intertwine political theory and contemporary art. Vesić is the president of the Association of Art Critics AICA Serbia, co-editor of the journal Red Thread (Istanbul), and a member of the advisory board of Mezosfera (Budapest). Her essay-book, On Neutrality (with Vladimir Jerić Vlidi and Rachel O’Reilly), is part of the Non-Aligned Modernity edition (MoCA, Belgrade, 2016). Her most recent exhibition In Collectivising (MG, Ljubljana, 2022) deals with feminist interventions into art-historical narrations of 20th century avant-garde art collectives.

Literature suggestions by Jelena Vesić for further reading:

Adajania, Nancy. „Globalism before Globalization – The ambivalent fate of Triennale India“, Western Artists and India: Creative Inspirations in Art and Design, 2013.

Azoulay, Ariella A. Unlearning Imperialism. 2019.

Césaire, Aimé. Discourse on Colonialism. Translated by Joan Pinkham. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2001.

Enwezor, Okwui; Siegel, Katy; Wilmes, Ulrich. Postwar – Art Between Atlantic and Pacific 1945-1965, HdK and Prestel, 2016.

Ferreira da Silva, Denise. ‘Unpayable Debt: Reading Scenes of Value against the Arrow of Time’. In The Documenta 14 Reader, edited by Documenta, Quinn Latimer, and Adam Szymczyk, 84–112. Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2017.

Ghouse, Nida; Guevara, Paz; Franke, Anselm; Majaca, Antonia. Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War, HKW and Sternberg Press, 2020.

Hadouchi, Olivier. Images of Non-Aligned and Tricontinental Struggles, Non Aligned Modernisms edition, Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, 2016.

Khouri, Khristine; Salti, Rasha. Past Disquiet: Artists, International Solidarity and Museums in Exile, Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, 2017.

Kulić, Vladimir. Building Babylon: Architecture, Hospitality, and the Non- Aligned Globalization. Non-Aligned modernisms edition Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade, 2015.

Kulić, Vladimir; Stierli, Martino. Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948-1980, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018

Linke, Armin; Travelling Communiqué Project Group; Eshun, Kodwo; Mende, Doreen; Tomić, Milica. Travelling Communiqué, Spector Books, 2016

Piškur, Bojana. Southern Constellations, Moderna Galerija, Ljubljana, 2017.

Plys, Kristin. Nostalgia for Futures Past. 2022.

Prashad, Vijay. The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World. New York; London: The New Press, 2008.

Sekulić, Dubravka. The Non-aligned (Round) Table and its Discontents, Fanzine RISO i prijatelji, 2021

Sladojević, Ana. „An Anticolonial Museum“, in: Europe Now, Decolonizing European Memory Cultures, Ducros, Hélène and Katrin Sieg, eds, CES, 2023. https://www.europenowjournal.org/2023/02/21/an-anticolonial-museum/

Sladojević, Ana. Images of Africa, Non-aligned Modernisms edition, Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, 2016.

Stubbs, Paul. ‘Socialist Yugoslavia and the Antinomies of the Non- Aligned Movement’. http://www.criticat-ac.ro/lefteast/yugoslavia-antino- mies-non-aligned-movement/

Szakacs, Eshter & Mohaiemen, Naeem. Solidarity in Messy Practice. 2021.

Vesić, Jelena; O’Reilly Rachel; Vladimir Jerić Vlidi. On Neutrality: The Letter From Melos, Non Aligned Modernisms edition, Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, 2016.

Vuković, Stevan. Non-aligned Nomos, Non Aligned Modernisms edition, Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, 2016.