Kris Dittel is a curator, writer, and publisher – but above all, she’s a thinker driven by curiosity and passion for her work, something I sensed immediately in the energy she brought to our meeting for this interview. Currently, she is a fellow at Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen in Innsbruck, where she is continuing her long-term project An Infinite Love Letter: On Desire, Intimacy, and the Politics of Love. In this project, she combines personal writing with theory to explore how love and desire shape our lives – not just in private, but also in society and politics.

Before our interview began, Kris invited me with excitement to her upcoming exhibition opening on June 12, 2025 at Kunstpavillon Innsbruck alongside the other Büchsenhausen fellows Felix Kalmenson, muSa mattiuzzi, and Ren Loren Britton. Kris sees this as a chance to step outside her usual practice as a curator. “As curators, we always have the possibility to hide behind other people’s work – we mediate and interpret, but we also sometimes hide behind it or stay in the background,” she told me. “Because the people you invite to work with are usually also people you’re interested in, so you let them speak for you. And now there is no such filter. This is something new for me, but it’s fun.”

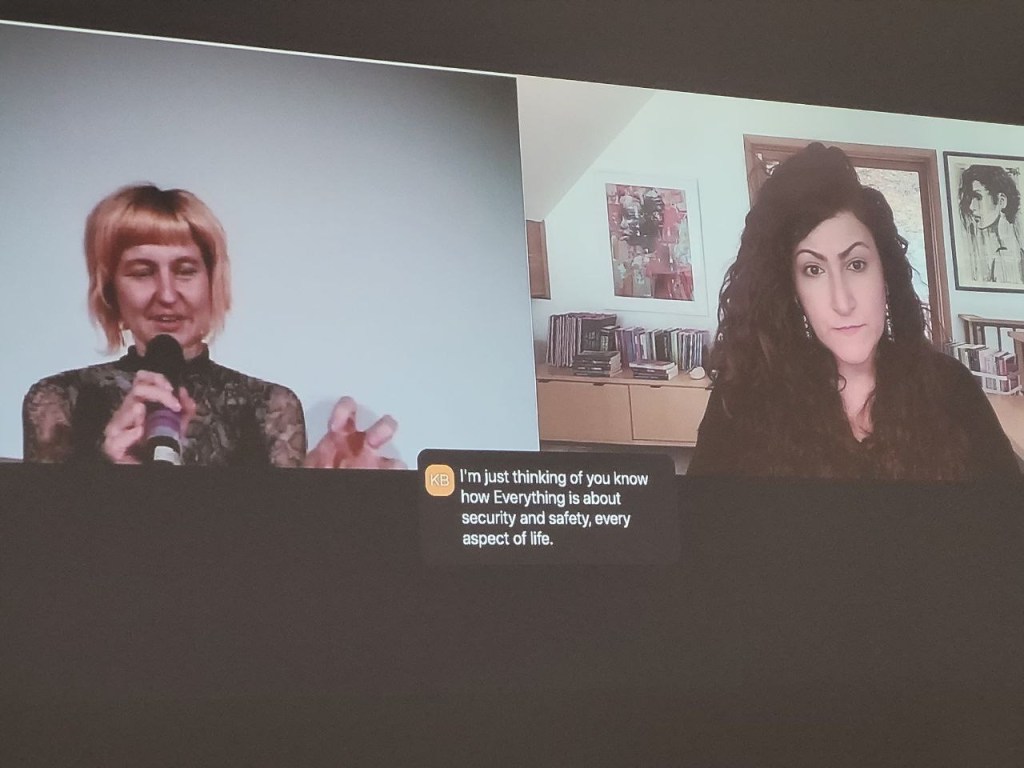

My actual first encounter with Kris was online, when I joined a public conversation she held in Büchsenhausen with clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst Avgi Saketopoulou. They spoke about Saketopoulou’s book Sexuality Beyond Consent: Risk, Race Traumatophilia (NYU Press 2023), where she introduces the idea of „limit consent“ – a form of consent that is not about self-protection, but about being open to risk and transformation. Their discussion reflected on trauma, risk, desire, and the role of art in allowing us to face what is unknown in ourselves and in others.

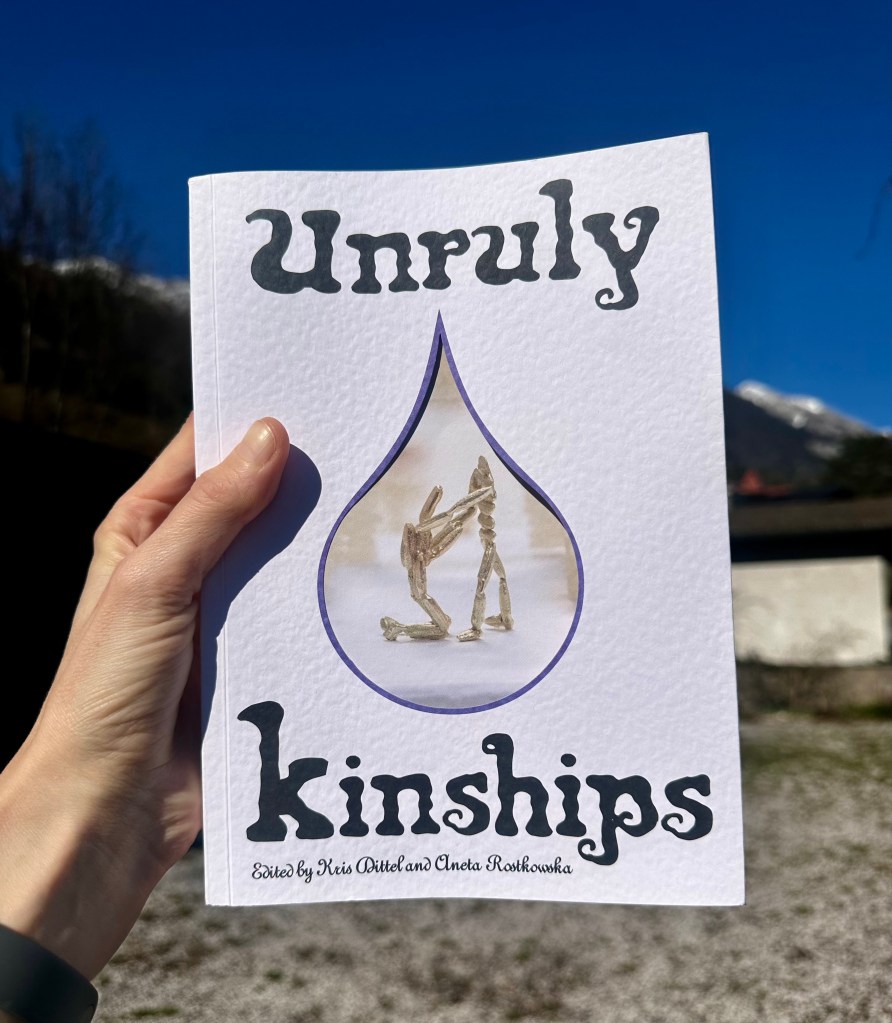

Kris’s work often grows from long-term research and takes diverse, interdisciplinary forms. Her most recent research project, Unruly Kinships (Jap Sam Books, 2025), co-curated with Aneta Rostkowska, explored relationships and family beyond traditional norms. The project unfolded as a study group, a series of open discussions, and an exhibition, and is now being published as a book.

In our conversation, Kris shares her curiosity about desire, the potential of taking risks, the problematics of romanticism, and how we might rethink or reimagine the ways we relate – to ourselves, to others, and to the world.

Dear Kris, can you tell us something about your work and your background?

Kris: First I studied economic theory, but I left tha behind and went back to study art theory and curating in Amsterdam. I’m originally from Slovakia. I moved to the Netherlands almost 16 years ago. I’m working mostly freelance, which I really enjoy. I find a lot of freedom in having the possibility to really do my own research and follow my interests without having to represent an institution _ I’m the institution of my own – but it’s also tough, financially, having to start from the scratch” with every project, and because my work tends to reflect my personal interests, it’s also requires a careful balance between how much you give of yourself and how much you allow the world into your thinking.

Now I am mainly working as a curator and editor. I don’t work as a stereotypical curator in the sense that I only produce exhibitions. Publishing is a major part of my work, and writing is increasingly becoming more important – which I love. As for me, an exhibition is not a finished work. I like when a project has different elements, and books are a little bit my crush. But it’s also a love-hate relationship because it takes so much time and work.

Would you say you have one specific research topic that always comes together in all your work from curating to writing?

Kris: The way I work, I usually have a main topic for several years, and this topic stays quite abstract. In the past, I worked with the question of value, and more recently with the topic of kinship, which has been on my mind for 5–6 years. First, I started with the publication The Material Kinship Reader (Onomatopee 2022, 2025), so-edited with artist Clem Edwards. Later on came the project Unruly Kinship; the related book was just published.

Can you tell us more about the project Unruly Kinship? How do you understand kinship?

Kris: The project started in 2022 with a public research series called Forms of Kinship. The idea was to look at forms of kinship that exist outside of the nuclear family and blood relations – how we can form social relations beyond these normative models. It was a joint inquiry with my colleague Aneta Rostkowska, who runs Temporary Gallery CCA in Cologne. With Forms of Kinship study group we wanted to open up our research trajectory to the public. We managed to get some funding and organized a monthly event series where we invited researchers, theorists, and artists to talk about the various ways we can think and talk about kinship.

For example, we had Sophie Lewis, who talked about her book Abolish the Family, we held a seminar with Prof. Mi You from the University of Kassel, who looked at the social history of the family as we know it today. With activist Georgy Mamedov, we had a workshop where we looked at our dreams – what our dreams tell us, and how they translate into our lives. It was a broad range of topics and events.

Overall, with this project we didn’t want to address kinship in a way that presents blueprints or models of alternative families or relationships. Instead, we focused on practitioners who are actively doing and practicing kinship in their work and lives. This went on for a year, and then the exhibition opened in 2023. That’s when we invited several artists to produce new works.

How did the artists interpret the topic of kinship? I saw that Selma Selman was also invited. (We did an interview with her about her exhibition at Kunstraum Innsbruck a couple of years ago.)

Kris: Yes, Selma Selman was one of the artists we invited. For this exhibition, she developed the work Motherboards, which made it to MoMA PS1 to perform the same piece. She invited her family members from Bosnia to perform with her, and brought in a huge pile of old computers. During the two days of performance, she and her family members dismantled these computers, extracting the motherboards – because they contain a tiny bit of gold.

Her initial plan was to produce an earring for her mother, but in the end – because it was such a lengthy process – she finished it a few months later and produced a golden nail that was placed in the institution at the Rijksakademie where she was a resident at the time.

It was also a disturbing performance, it was very noisy, and watching people doing this kind of heavy labor during the exhibition opening was unsettling. You become aware of your own position: now we are in an art space watching a performance, but outside that context, we might not value the labor it entailed. I’m interested in that moment that makes you uncomfortable, that twists something inside you. Selma’s work in general takes this kind of risk.

What’s your personal interest in the topic of kinship? You mentioned it came out of a personal conversation…

Kris: I truly value the freedom to work on topics I have a personal connection to. One of the reasons why the topic of kinship was and remains important to me is that I’ve never felt at ease with the model of the “good life” where you supposed to form a nuclear family and follow that path in life. I’ve always sought out queer ways of relating – not necessarily “alternatives”, as I find that word limiting – but rather different kinds of relating that aren’t imposed or presented as ideals we should strive for.

It doesn’t mean we have to discard the idea of the nuclear family entirely, but what if it’s not the only possibility of being in relation with others? Many theoreticians have addressed this issue. I think even Engels said that the monogamous nuclear family is the smallest building of capitalism (The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, 1877). It produces workers but also hierarchies, such as the patriarchy.

I say nothing new by stating that increasingly we live in a world marked by exhaustion. At the same time, we are increasingly forced to rely on ourselves instead of a communal care. You have to raise your children, take them to school, and at the same time be a full-time professional at work, run a household, etc. There’s an increasing compartmentalization of society and mounting pressure on the individual. At the same time, there’s a growing need and desire to be more connected – yet structurally, and systematically, we are being pulled apart.

So I’m asking: what can we do with these forms of desire, to connect, even in small ways? What kinds of relations do we truly value? It already makes some impact – a drift alongside a wave of thinkers, makers, practitioners who are actually exploring and imagining other ways of relating to one another, even if only temporary, considering the project’s timeframe.

What are you actually doing now in your fellowship at Büchsenhausen? You’re carrying out a project titled “An Infinite Love Letter”? Is it related to Unruly Kinships?

Kris: Over the past years, while working on the Unruly Kinships exhibition, I started the writing project An Infinite Love Letter. The way I write connects the personal and the theoretical. It’s not about wanting to theorize something or taking the position of an observer. My writing reflects on events, books I’ve read, artworks, or conversations or encounters I’ve had. I call it a love letter because there’s an intimacy implied in that form, the letter is addressed to the reader. The fragments are like a puzzle; most of the topics relate to love and desire, and how love can have a political potential.

There are many thinkers like Laurent Berlant, for instance, who theorizes love in a transformative way. I’m interested in the state of love that allows people to take risks – it opens the possibility for transformation, where people lose their minds and do things they otherwise wouldn’t.

[…] How does one learn to want something? Did I want a pink ball of candyfloss because I was enchanted by its forms, or did I want it because all the other kids had it and I was met with a sense of approval, a permission to want it, from the outside world? How can I say whether this need and want is mine, that it is real? […] (Kris Dittel, „An Infinite Love Letter“, in: Unruly Kinships, 2025. p. 90.)

Through the writing process, I realized I’m now less interested in love and more in desire – as a driving force of love. Desires are not as straightforward, you might think you know what you want, but actually, it’s quite a difficult task to attune to one’s desires. I became more interested in how we find the object of desire and what it can be.

What can it be – an object of desire?

Kris: It can be a person, a thing, a fetish object, an idea or ideal – all of these things.

As part of your fellowship, you invited psychoanalyst and theorist Avgi Saketopoulou for a discussion on her book Sexuality Beyond Consent: Risk, Race, Traumatophilia. How does her work relate to your practice and interests?

Kris: What drew me to her work in the first place is the her engagement with risk. We are becoming increasingly risk-averse as a society. Of course, I see this reflected in the art world too – there’s much less room to take risks as a maker or practitioner. You’re afraid of saying something wrong and being “canceled,” or doing something unexpected that people can’t immediately make sense of, or perhaps being misunderstood. There’s a tendency to create a fixed meaning and to make art safe – explaining in advance what a work does, or a kind of excessive cushioning. While that can be important, it can also feel suffocating.

This idea of risk resonates with me far beyond the realm of art. We’re building a society that tries to eliminate the unknown. Avgi Saketopoulou talks about risk in a way that aligns with my own wish to defend risk-taking in art and beyond. I notice a kind of apathy or disinterest growing – also among my students. People are increasing bored of art that’s presented in major institutions. I think that boredom comes from not being able to experience something truly transformative or disturbing. There’s a lack of artworks that challenge us or leave us without immediate conclusions, or even “coming undone”. That’s the experience Avgi explores in her writing, and it’s something I find incredibly compelling.

I came across Avgis book last year and immediately thought, “This is exactly what I’ve been thinking.” Sometimes, you encounter an artwork or text that expresses something you felt but haven’t yet been able to articulate. She comes from a psychoanalytic background, which personally fascinates me – how she uses that framework to understand what happens to us when we encounter something that overwhelms us.

Can you share a paragraph from Avgi’s book that inspired your work?

Kris: Yes, there are so many!

“My interest lies in the way some art and performance achieve their effects on us not because they make contact with some formed content or memory in us that they activate but by creating dizzyingly intense experiences that meet us at the core of our being.” (Avgi Saketopoulou, p. 17.)

“We are all routinely humbled by how our experience of autonomy and sense of sovereignty are delimited by the unexpected and the unforeseen arising in our encounter with the other. Such contact with opacity and with the unknown may whet appetites we did not know we had, embroiling us in situations we may have not chosen to get tangled into. We do not always get to draft the conditions of our interpersonal encounters, encounters to which we have to sometimes submit, sometimes surrender, to get part of what we need or want.” (Avgi Saketopoulou, p. 21.)

What is it actually that fascinates you so much about taking risks?

Kris: In a way, you could say it’s a privilege to have the choice to take risks. However, for many people, it’s not a choice at all. If you don’t have much to lose, you might risk even more, or simply it’s the way you are surviving. That’s why talking about risk can be tricky. The real risk, in some ways, would be to let go of the privilege that allows you to take risks in the first place.

I’d encourage people not to take risks just for the sake of it, but to think about the purpose behind it – and ideally it’s a transformation, or even shattering of our egos. What is it we need to leave behind? What are the costs?

What I found in Avgi’s work – and what resonates deeply with me – is that risk allows us to touch our ego, our deeply embedded belief systems that we’re not even fully aware of. Taking a risk enables us to have an experience that might change something within ourselves that we otherwise can’t.

How do you see risk-taking as a political potential – not only on the individual level, but more broadly?

Kris: When we talk about politics, for me it doesn’t have to be macro-political. The politics of the self is already deeply political. The way you allow yourself to process experiences, and what you choose to discard – that’s always already political.

I’m not trying to make a grand, groundbreaking political statement. I mean, I could – we live in an increasingly fascist world where genocide is being broadcasted live on our phone screens – I’m talking about Palestine. But the question is: how can we get out of this state of passivity? I believe it starts with the self.

There’s this slogan from the 1960s: “The personal is political.” That’s also where my interest in the politics of love came from, which later shifted more toward thinking about desire. I also realized that when I talked about love, I had to do a lot of groundwork to explain that I wasn’t talking about romance or the stereotypical heteronormative couple. At the same time it’s good to acknowledge how ideas of romance are so deeply embedded in all of us – including me.

Desire, for me, has become a more open and generative concept. It’s about our needs, what do we want? I’m trying to get away with this idea of romance altogether.

So would you say you’re not a romantic person?

Kris: I don’t think I am. That sounds terrible, maybe! But I’m really interested in authenticity and the sincerity of a relationship, rather than its performance. When we think of romance, we immediately get these culturally embedded images – and that’s exactly why I prefer not to talk about romance. It’s not that I reject everything about it – I mean, it’s lovely to get a bucket of roses, I also love that – but I’m wary of how it becomes a social performance rather than a real connection.

It’s less about truly seeing someone or understanding what they need, and more about reenacting something that feels comforting or familiar. And again, there’s nothing wrong with having those desires. The problem starts when it becomes a performance of something you think that is expected from you – a script we follow rather than something we feel.

Did you have to actively unlearn that?

Kris: Definitely. I grew up reading a lot of novels and watching romantic films. Most of them presented a very limited way of performing gender and relationships. That’s fine as one possibility – but it’s almost become a rule, it’s the only dominant narrative. I had to unlearn that idea. I don’t want to fight romance, but I want to ask: How can we truly see each other? Of course, we’ll never fully understand another person – we can’t even fully understand ourselves. But we can try.

Criticizing the idea of romanticism reminds me of Eva Illouz’s book Consuming the Romantic Utopia: Love and the Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. Is that also related to your work?

Kris: She’s a bit too anthropological for me. I think she’s more of an observer than a critical thinker. I read the book, and while she describes what’s happening and reflects on it, she seems to take for granted how we form relationships today. It’s descriptive rather than transformative in my view.

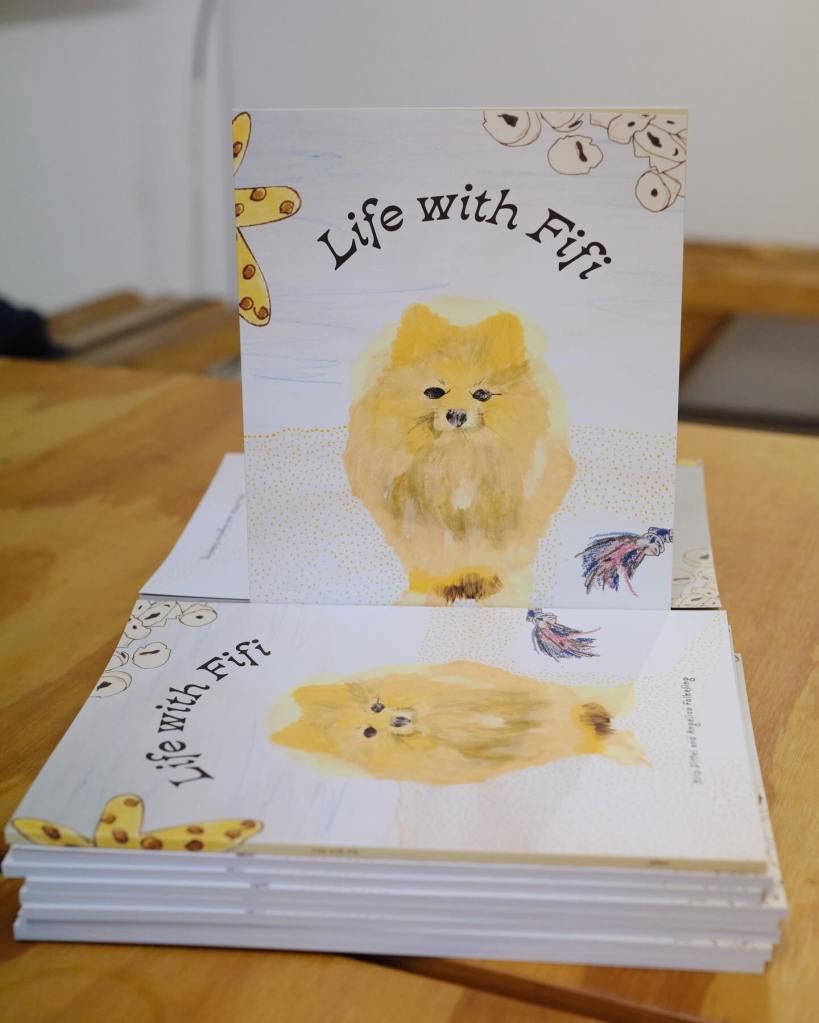

I saw you also wrote a children’s book – which you describe as a „book for everyone“. Can you tell us more about this project? Is it connected to your broader research on relationships?

Kris: It’s called Life with Fifi, and Fifi is my dog. I co-authored the book with my friend Angelica Falkeling, who is an artist. We also live together and a few years ago, we decided to get a dog together. I have an anecdote that ties to what we were talking about earlier, the challenge of imagining forms of relationships beyond the blueprints we grew up with: when we got Fifi, everyone suddenly assumed we were a couple. We constantly had to explain: no, we’re just friends who live together and have a dog together. It was really interesting to observe how quickly people projected a normative idea of family onto us. It made me think about how conditioned we are to assume that caregiving always imply a romantic or nuclear-family dynamic, even in its deviant form as a “lesbian couple and their pet-child”. But you can have deep, meaningful, caring relationships outside of that framework too.

So, Angelica had recently returned to her drawing practice, and when we got the dog, she began sketching small moments from our life with Fifi. At some point, we thought – why don’t we turn this into a children’s book? But I prefer to call it a book for everyone. Children’s books are often limited by age categories, and there’s this idea that you should grow out of certain things or understand certain things at a certain age. I remember as a child feeling a kind of shame when I still wanted to play with toys I was supposedly too old for.

The book has several layers, or narrative layers, it follows one day in the life of Fifi – from morning to evening. It also talks about dogs in general, how they experience the world, their senses, what it means to take care of another being.

The idea behind working on a book that is “for everyone” was to consider it as an offering, to invite curiosity and to let each reader take away what they will.

| Brigitte Egger

BIOS

Kris Dittel

(The Netherlands/Slovakia) is a curator, editor and writer. Her practice is driven by long-term research projects that materialize in various forms, including exhibitions, publications, public events, performances, texts, talks, and more.

Her most recent project, Unruly Kinships, included an exhibition, a study group series, and an event program, co-curated with Aneta Rostkowska (Temporary Gallery CCA, Cologne 2022-24). This project explored possibilities of kinship beyond the nuclear family and examined ways we may form relations with/in the world.

With Clem Edwards, Kris Dittel co-edited The Material Kinship Reader (Onomatopee, 2022), which addresses material relations beyond extraction and kinship beyond the nuclear family. Currently, she is co-editing two volumes: Unruly Kinships (Jap Sam Books, 2024) with Aneta Rotskowska, and a children’s book, Life with Fifi (Böks, 2024), with Angelica Falkeling.

Alongside her curatorial and editorial work, Kris Dittel is also an active educator, primarily serving as a research supervisor and writing tutor.

Avgi Saketopoulou

is a Cypriot and Greek clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst practicing in NY. She serves on the faculty of the NYU Postdoctoral Program in Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis. Her publications have received numerous prizes, including twice the annual prize of the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, the Ralph Roughton Award, and the Symonds Prize. Her interview on psychoanalysis is in the permanent holdings of the Freud Museum (Vienna) and her monograph, Sexuality Beyond Consent: Risk, Race, Traumatophilia (2023) braids psychoanalysis with performance studies, philosophy, and queer of color critique to explore the vicissitudes of overwhelm and repetition. She is co-author, with Ann Pellegrini, of Gender Without Identity, which includes a re-worked version of the essay for which the two authors received the International Psychoanalytical Association’s First Tiresias Prize. Avgi Saketopoulou is in critical conversation with Dominique Scarfone in the book The Reality of the Message: Psychoanalysis in the wake of Jean Laplanche, and is currently working on her next publication project provisionally titled The Offer of Sadism: The Aesthetics of Confusion and Opacity.