We live in times where division and racism are constantly rising. Despite the significant investment in cultural remembrance practices, our societies face challenges when it comes to a peaceful coexistence among people from different cultural backgrounds. How can we overcome such devisions and separations?

One example of dealing with these themes in an artistic way is the current exhibition at Kunstpavillon Innsbruck, running until August 10th, 2024 where the Büchsenhausen Fellowship Programme for Art and Theory 2023-24 presents The Secret Life of Plants and Trees. We have already published in-depth interviews with two of the participating artists and theorists Agil Abdullayev and Tatiana Fiodorova-Lefter. In this article, we highlight the third fellow, Hori Izhaki, who, through her poetic multimedia installation, faces the complexity of her identity as an Arab Jew with an Israeli passport. Her exhibition, titled illi yidri willi ma yidri hafnat ʻadas (= the one who knows, knows, and the one who doesn’t know, a handful of lentils), refers to an Iraqi idiom suggesting significant meaning concealed behind something seemingly trivial – mirroring the metaphorical depth of her art. In our interview, Hori Izhaki shares personal stories about how her (given) identity – depending on her national and societal contexts – influences her experiences and perception of life.

Dear Hori, in your project you focus on identity politics, specifically you name the identity of the “Arab Jew”. Why is this such a central topic for you?

I would start by explaining why I emphasize on naming it this way, especially because the early Zionists, who were mainly Europeans, made a concerted effort not to name it this way. They worked hard to exclude the Arab from the Jew, giving us terms like „Mizrahi“, which means „eastern“ in Hebrew, even though many of us come from the west. There is a long history of Jewish people in the Arab lands; they were respected, had their own laws, privileges, and a kind of autonomy that was different from Europe. The Zionists in Israel excluded this history of the Arab Jews, which conveniently framed the local Arab as the enemy. In doing so, they created a sense of self-hatred or detachment among the Arab Jews. Many of them immigrated as doctors or academics but could not practice their professions because they had not studied under the European academy. Instead, they were forced into other types of labor. I feel sorry for the first generation of Arab Jews who came to Israel because they were looked down upon and were positioned (one could argue, still today) beneath the European Jews.

Can you tell us something about the scale of Arab Jewish migration to Israel and the primary motivations behind it? How did these migrations impact the country?

The majority of Israel’s population consists of Arab Jews, just above 50%. One of the reasons why the Zionists brought Arab Jews was to alter the demographic balance between Muslims and Jews in Israel. European Jews were not numerous enough; some disagreed with Zionism and migrated to the US. Zionism, based in late 19th/early 20th-century Europe, was rooted in utopian ideals. Utopianism has its own issues, as utopia is inherently doomed to fail and detached from its surrounding reality. However, European Jews turned it into a practice, and this practice influenced the formation of the land of Israel. They didn’t want Arab Jews, not for their significant culture and history, nor for their connection to the Middle East. They needed them to change the demographic situation but also for carrying out labor work. One of the tasks they had to perform was planting pine trees, which in a way became the spirit of my entire work. Through my research, I discovered that my grandfather was among those assigned to plant pine trees in Israel, and he hated it.

Regarding your personal history – if you want to share – when and why did your parents, both Arab Jews, move to Israel?

My mother immigrated from Morocco in the 1960s with her family, and my father’s family arrived from Iraq in the early 1950s. This migration was influenced by various factors, including increasing persecution of Jews in the Arab world following 1948. The Zionists‘ efforts to attract Arab Jews were part of a broader strategy to shift demographic balances and integrate them into the newly established state. Gradually, Arab Jews were viewed differently, because they were no longer considered part of the Arab land or nation. For example, Iraqi Jews were seen as Zionists, collaborators with Israel (the Jewish land). In Iraq, where my father’s family is from, the Zionists even bombed a Jewish synagogue to create fear among the Jewish community there.

Returning to the first question – this is why it’s important for me to say „Arab Jew“. My father could not see himself as Arab. For him, being an Arab meant not being Israeli, and he always had to prove his loyalty to Israel. This loyalty, in an absurd way, often meant self-hatred. Part of not belonging was not being like European Jews, as neither he nor his family had been in the Holocaust. This is why we needed to carry the memory of the Holocaust on ourselves. Until recently, my father would say, „I was in the Holocaust“, but no, he was not, and he does not need to be to belong. Even as a child, I would imagine myself remembering myself in a concentration camp, being in a cold bunk bed.

In my work, I am also challenging the idea of identity politics. Identity politics can be very dangerous, and one can see this now in the dichotomous ideology, such as “for Israel”/”against Palestine” and vice versa. It’s becoming so verrückt, with no room for complexity or questioning. Everything is clear and simple, black or white, good or bad, and I believe identity politics play a role in this. The sad thing is that the left is beginning to sound like the right-wing and racist ideologies, which worries me, and I would like to question this.

What do you believe makes identity politics so compelling and influential today? How does it shape our understanding of group belonging and individual identity?

Feeling a sense of belonging to a group and reclaiming our rights is empowering and positive, but one should be careful to what extent one builds their own walls of differentiation. I’m thinking immediately of a book by Eva Illouz that I recently read. It’s titled „The Emotional Life of Populism: How Fear, Disgust, Resentment, and Love Undermine Democracy,“ and I also think the usage of feelings is hidden in identity politics. Illouz touches on this structure in a very profound way. There is something about belonging to a group that really minimizes our critique of ideology. Poured into a mold, we lose the ability to think broader and see farther and therefore mistake what’s actually in our interest.

I watched a very interesting interview on the Afikra podcast with Omar Kholeif, titled “Redefining Arabness in the Digital Age: On the Arab Identity” from August 2023, where he asks, ‘What is an Arab?’. As part of his answer, he described when he himself asked his father the same question, and his father’s answer was, „What do you mean? Palestine, Palestine is the metaphor (the metaphor of being an Arab)“. In contrast, Omar claimed that being Arab is a state of choosing to become Arab. In this way, Omar Kholeif offers us an open idea of identity and belonging. I found in it a different understanding of Arab identity, it feels inclusive for me, suggesting that there is a place also for the Arab Jew in the Arab identity (because it’s a state of choosing to be).

When you applied for the Büchsenhausen Fellowship, it was before October 7th. How did your feelings about your project change when the war started? Did you have any concerns about carrying it out due to the sensitivity of the topic?

I designed a shirt as part of my work, on which was written in Arabic letters „I’m also an Arab“. I wore it so proudly everywhere, from Berlin to Israel, which started many conversations with people and made me feel a sense of belonging. Before the 7th of October, I went to Israel/Palestine to film; on many occasions, I proudly wore this shirt. I felt (maybe naively) it could make a change, because when we see ourselves also as Arabs, we grow empathy and solidarity. On the 7th of October, I was sitting in a very small and unsafe shelter; bombs were shaking the entire igloo-like concrete shell when a house next to us was completely demolished and a woman died in it. My brother decided that we had to leave, he drove us to a safer place, two loads under a sky full of rocket shooting. On the way, when we were passing through an army checkpoint, I immediately had to cover my shirt. I was afraid that they would see the Arabic writing and they would attack me. At that moment, all the hope of my project seemed to soak away, and I knew I was going to face a different reality. It was unimaginable; nothing like that had ever happened to me in my life. It was like the dawn of days, and it makes me think of the Palestinian people living like this for the past ten months. I cannot imagine what goes on in their minds, hearts, and bodies, when for me one day was so horrendous. This thought leaves no air in me. Of course, I was also afraid that everything said can add fuel and I just wanted to moan.

When I think, „I am an Arab,“ what comes to my mind at first is not my Iraqi family; I think about the Palestinian people and neighboring countries. This is the connection I have learned to the word „Arab“. It took me a long time to want to be „Mizrahi“, and when I wanted it, only then did I understand that it means I am an Arab with Arab history. For a long time, I tried to become a white „Ashkenazi“ European Jew. I did everything in my power to pass as one.

You are based in Berlin now. I remember in your first talk at Büchsenhausen, you mentioned how different German authorities and institutions would treat you depending on if they knew that you have a Jewish identity…

Yes, the first thing they do is look at you, and obviously, when I did my Anmeldung in Neukölln, it was very clear that I belonged to the Arabs. I think, therefore, the woman at the counter was immediately not willing to help me. She was very rude, saying, „In Deutschland muss man Deutsch sprechen“. I cried because I didn’t understand what she was saying; it sounded very aggressive. She sent me home. I prepared everything carefully and in order, and on top of it, I placed my passport. Then I went there again. It was the same woman, and the moment she saw my Israeli passport, she completely changed. All of a sudden, she was very friendly. She even spoke to me in English, offering help to fill in the rest. She didn’t recognize me, but I recognized her, as she sees many like me; I saw her as one. I didn’t want to sabotage my Anmeldung, so I stayed quiet. But I experienced more occasions like this, and unfortunately, sometimes worse. It’s interesting to be in this dual position.

Germany invests significantly in Holocaust memorialization, yet there are rising concerns about increasing racism in the country. How do you perceive the effectiveness of these memorialization practices in addressing contemporary issues of racism and discrimination?

Germany cleanses itself through the remembrance of the Holocaust in many ways, but this culture doesn’t always translate into meaningful change or acceptance. This is now especially evident in the experiences of Arab people. I wasn’t Jewish for 17 years because I disagreed with Judaism and tried to remove this status from my documents. However, I realized that avoiding this identity came with significant disadvantages and losing my rights. So, I thought, I’m not Jewish, but I’m also not stupid. I kept it officially, and it was enough for me to know I’m not Jewish.

I didn’t identify myself as a Jew until I moved to Germany. Five years ago, I got canceled as part of a group – we were a group of women artists and thinkers called “Unlearning Zionism”. We did a conference with intellectuals relearning the history that was indoctrinated to us. They stopped us and called us antisemites. This was the point where we sent a statement to the press saying we were Israeli-Jewish women wanting to learn our true history. I finally had to consent to be Jewish. So, Germany made me a Jew again. But I also understood the power I have, not just as a Jew, but as an Arab Jew.

You wrote this text _augmented_memory:_ ARAB_in_the_ALPS_ [IMpostER] on the phenomenon of memorialization in Europe. You mention in it the concept of “multi-directional memory” by Michael Rothberg – what is it about and is this something that you would support?

I wrote this at the beginning of my project; I think the relationship of my work to Rothberg has changed a bit towards the end, but his core ideas remain relevant to me. Multidirectional memory deals with the fact that different violent histories confront each other in the public sphere. Mainly, Rothbergs concept is about reading one historical event through the lens of other historical events, like the Holocaust and slavery. What I take from it is mostly how memory, on the one hand, is being sealed, purified, and unable to be penetrated by its political and cultural power, keeping us limited. I move away from this; I emphasize the need for a multitude of histories, even when they contradict each other, and the undisputed need for multiple narratives in collective memory and society. As even life is often contradictory, also in micro personal relationships.

Growing up in Israel, a place that has been so homogenized, I was confronted with a historical narrative that leads only to one direction, which makes me sad. I wish that in some years Palestinians would speak Hebrew and Israelis would speak Arabic. It’s not about them and us. I speak German, and I’m happy that there is a place for Jewish people to come back to Germany, and that gives me hope. I hope we will do a better Aufarbeitung with the Palestinians, and that it would lead to a place where we redeem ourselves from this, not for the sake of redemption, but for our living together. All in all, it’s a beautiful place and it’s home, but not like this (I mean also before 7th October). At the moment, I don’t have a home at all. The home is on fire. This is very sad, and I’m ashamed.

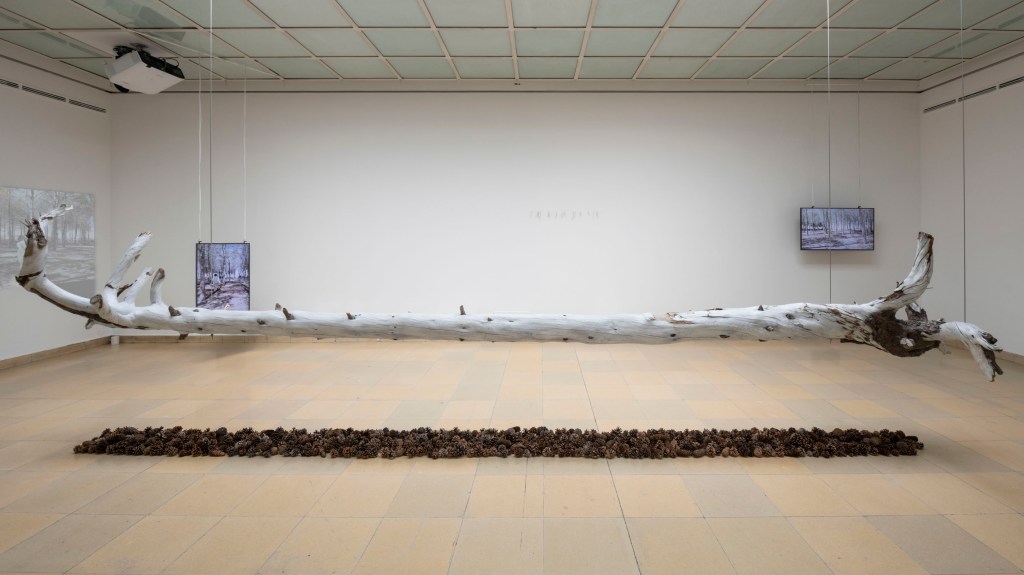

Coming back to your exhibition at Kunstpavillon and the story with the pine tree – as central object you placed a dead tree hanging in the middle of the space, underneath you created a path of pinecones. You already mentioned it, but can you tell us more about how this object is related to the Arab Jew identity?

You could read about the significance of the pine tree in the settlement of Zionists in the exhibition reader*, but the image of the Arab Jew planting those European trees in the Middle East, like planting European memory into themselves, is stronger than any explanation. The installation features a complete tree, with its roots and canopy symbolizing the dual sense of ‚Heimat‘. Finding a whole tree was challenging; many were broken; it took me many walks in the woods. There was one other tree in competition; it was bigger and more showy, but the other one was very gentle and precise. For me, the first one reminded me of the male and the second was feminine. So, I went with the feminine one; I also wanted a feminine action.

Hannah Arendt talks about the division of action, labor, and work. For me, all three were intertwined in what we did: an action with a story that we create, an action that reveals to us the meaning of our labor. A work ending with the object, something that carries on a story to the world. With this project, it was relevant to me to have social significance. Together with eight women, we carried this tree through the forest in Absam, to Rum, and to Innsbruck. The women all came from different places, ages, and backgrounds; I met them on different occasions in Innsbruck, but all had shown me something and had the power to go deep. We gathered before to talk about what we do with this action.

Would you say this action was also something spiritual, something like a ritual?

Definitely. I can definitely say it was a ritual but also very much a spiritual action. We were eight women carrying this heavy tree for many kilometers. It was so powerful how the weight was always shifting. We decided that each time someone felt the weight was not balanced, we would stop and put the tree down. It was amazing that sometimes a woman would say stop because the tree felt too light for too long, meaning somebody else was carrying the weight. There were so many moments of feminine being, feminine communication, moments of collectiveness, and using Donna Haraway’s concept of temporal kinship. That was so beautiful for me.

This idea of carrying the tree together is like carrying the entirety of the multitude of narratives, of memories and contradictions. It is carrying diversity, and for that, one doesn’t need force but strength. This work is not just for the Israelis or Arab Jews; it’s also for the Europeans to understand what happens when you create a hegemonic society with only one story, one history, what happens when we do integration instead of inclusion.

After this exhibition, the tree will be presented at the Jüdisches Museum Hohenems and then it will travel to Israel. Why is it important for you to bring it to Israel and to exhibit it there?

Because Israel is its righteous place. This entire action was not a Gegenaction but a Transaction, to what the Zionists did. They brought pine trees and enforced them into Palestine, into the Middle Eastern land where they were not endemic to the environment. There is a very nice quote in the text „The Forest’s Many Shades of Green“ by Alon Tal. He quotes the director of the Land and Afforestation Department of the Jewish National Fund (JNF) who would write in his diary: “One morning, I’m coming up the road from the train, filled with blissful expectations of ‘the forest’. I climb, skipping up the incline to see my soft, newly nurtured darlings. But then they came into view and my eyes turned black. The green saplings had turned brown, except for a few isolated ones here and there, and from the heights I could hear the ridicule of the Angel of Death”. About 70 – 80 % of all the planted pine trees die in every planting round in Israel. But the Zionists wanted to create utopia, they wanted Europe, they wanted the Alps. Related to this, there is also a beautiful poem by the Zionist poet Lea Goldberg. She talks about how these pine trees related to her two different and connected roots:

Here I will not hear the cuckoo’s call.

Here the tree will not wear a cap of snow,

But it is here in the shade of these pine trees

My whole childhood resurrects.

The chiming of the needles: once upon a time

I called the distance of snow a homeland,

The greenish ice that fetters the brook,

To the poem’s tongue in a foreign land.

Perhaps only birds of travel know –

When they are suspended between earth and sky –

That pain of two homelands.

With you I was planted twice,

With you I grew, pines,

And my roots, are in two different landscapes.

With the two roots, she is in between these two Heimat, Israel and Europe. Similarly, my tree with its two edges stands for this duality of the Arab Jew’s two roots, but also for this utopia of Europe in the Middle East and the inevitable connection between them.

In Israel, the tree will be exhibited in the Mishkan Museum of Art in Ein Harod, which is the first museum that was built before the formation of Israel by the Zionists. They understood that if you want to create a nation, you need to create culture, so they brought European culture to the Middle East by creating this museum. I reached out to Avi Lubin when I read that he had become the new director and understood where he wants to take the museum. I thought this museum was the right place for the tree. Until Avi, this museum predominantly showed European art, and when it didn’t, it looked at Arabic art in a very exotic way. For me, it’s part of the action that the tree comes to Israel. It needs to travel there. It’s a poetic work, and the sentence ends in this space. I must say it is also a very beautiful museum.

You just mentioned the poetic aspect of your work – for me, that’s how I perceived your whole exhibition, each object could work as a metaphor and be interpreted in various ways, like a poem. Is there an object that you favor the most?

I am a great believer in poetry. It is not an „in-your-face“ action and, therefore, allows one to feel through one’s perception the many folds of the work.

It is difficult to say. Probably the tree, but also the pinecones and the whole action of collecting them. They are a mixture of pinecones from Israel and Austria. There are also the videos in the exhibition, which show different parts of my family collecting the pinecones. This collecting of non-food items, something that is essentially empty, is something that really moves me.

I also like the work ‘Ana’ [Arabic for ‘I’]** because it’s just so precise. But I don’t know; there are a lot of moments I like, and they rotate in favoring the most. I have my own relationship to each of them.

Yes, I wanted to mention your work „Ana“** as I found it very beautifully done. Also the surrounding window that was cut out from the wall, making the previous layers of paint visible, the layers of history of all exhibitions done in this space…

Exactly, and you know, we even found a small pinecone in the wall. It was amazing. The window, on the one hand, shows the history of the place, while on the other hand, it creates a false history of Arabic architecture. The plant named „Jewish Wanderer“ reflects the Jewish part in me that overshadows the Arabic. I found it interesting that there was a symbolic fear of killing the Jewish Wanderer plant, as there was a real concern among the crew in the Kunstpavillon – they worried about what it would mean if they killed the plant (laughs).

| Brigitte Egger

BIO

HORI IZHAKI

is a multidisciplinary artist from Tel Aviv Jaffa, who is currently based in Berlin. Her work has been shown in solo and group exhibitions in museums, galleries, festivals and art fairs in the Middle East and around Europe, including the Jewish Museum Berlin, Volkskundemuseum Wien and the CLB Gallery Berlin.

With her art, she arrives in temporal mechanisms, structures and arrangements she builds to fall and fail (like any utopia). Inspired by the mechanisms of sociological phenomena, their grounding in social rituals and the possibility to play with them, she investigates issues of identity in relation to memory (collective as personal), colonialism of the (female) body, its representation and trauma.

For Izhaki, nesting her works between disciplines is a choice aiding interrogation. Embracing the unresolvable question of what starts what, the media emerges from the theme and the theme is born from the media. She works with performance, installation, language, video, sculpture and temporarily emerging communities of participation in the intersection between the natural, the technological and the symbolic.

Notes

* ’Izhaki takes up the leitmotif of (European) conifers, which were systematically planted by the Jewish National Fund (JNF) on land purchased for settlers in Israel-Palestine since the beginning of the 20th century, along with other tree species, and enjoyed great popularity due to their appearance and ability to protect the soil from erosion. Many of Israel’s parks still contain trees planted on behalf of the JNF. But behind the superficial banality of a conifer lies a settlement policy that, from the very beginning, was concerned with securing living space for immigrant settlers. In addition, for many Jewish immigrants from (northern) Europe, Russia, or North America, the conifer was a kind of reminder of their former homeland. The new settlement thus evoked a sense of familiarity. Izhaki takes up this historical fact, but in a very different way: She takes a carefully selected, already dead tree trunk from the bed of the Fallbach creek near Innsbruck with the intention of taking it to Israel-Palestine in a non-Zionist manner after the exhibition. The tree trunk, which still has roots and crowns at both ends, now “floats” in the middle of the back room of the Kunstpavillon above the cone-covered floor, becoming a performative body onto which the artist transfers the attribution of identity she has experienced. The trunk was taken from the creek bed by eight women dressed in white, carried through the forest into the city and brought into the exhibition space, where Izhaki whitened the tree’s bark. Upon closer inspection, the brittleness, scars, and the fragility revealed in the myriad details of the tree’s body convey a haunting sense of vulnerability and yet unwavering endurance. Around the floating tree, a multimedia arrangement unfolds that, similar to memory processes, shifts and blurs the boundaries between reality and truth, between the experienced and the imagined’

(Andrei Siclodi, exhibition reader)

** Ana (= Arabic: “I”) materializes as an Arabic window milled into the wall of the Kunstpavillon. At its center, is a delicate brass structure reminiscent of the Arabic letters Alif and Nun (= “I”) that supports two small water jars from which delicate Tradescantia zebrina plants, also known as “„the wandering Jew,” grow. Thus, Ana combines Jewish and Arab identity markers in a metaphorically charged, performative in-situ intervention: Over time, the “wandering Jew” plant will overgrow the Arabic “I” and eventually remove it from view, while the supporting Arabic structure remains. Ana also plays with the idea of a history that never happened— the inscription of Arab architectural and everyday traditions into the history of Central Europe.

(Andrei Siclodi, exhibition reader)