Whoever entered the Leokino cinema during the 34th International Film Festival Innsbruck (IFFI) most likely didn’t miss the bright neon-green posters displaying just one short sentence written in a gothic-style font: „The Past Is Now“ – this year’s festival motto. It almost seems as if the intense color is pulling the past into our overstimulating present.

From June 4th to 9th, more than 60 films from around the world were shown at the IFFI. In line with this year’s motto, many of them invited us to think about how the past continues to shape the present, and the future.

Festival director Anna Ladinig writes in the program booklet:

“In today’s burgeoning flood of media content, the boundaries between past and present become blurred; in re- ciprocal dialogue, documented testimo- nies, from historical archives to living memory, are being reconsidered, restruc- tured and re-examined.”

And which film could reflect this idea better than Tamara Stepanyan’s „My Armenian Phantoms“. In a very personal way, Tamara enters through her film a dialogue with her father, Vigen Stepanyan, a well-known Armenian actor who passed away in 2020. Using archival footage, she narrates the story of her family, her country, and the history of Armenian cinema – while also reflecting on her own role as a filmmaker.

When I watched My Armenian Phantoms at the festival, the film’s intimate and poetic form left a strong impression. One could even feel it in the atmosphere that followed its closing scene – the audience seemed deeply moved by the emotional journey Tamara shared. That didn’t come surprisingly though, as the filmmaker had pointed out already before the screening that for her, presenting this personal film in public, almost feels like standing naked in front of the audience.

After the screening, Tamara Stepanyan joined Ramona Rakić from the IFFI team for a short Q&A. We gained more insights into her approach as well as some personal anecdotes related to the filmmaking process – but afterwards, I still found myself with so many questions, the conversation could easily have lasted as long as the film itself.

Once again, IFFI created a space for exchange between filmmakers and film enthusiasts in an almost family-like atmosphere, where encounters and relationships became possible across borders – and this all within the microcosm of Innsbruck’s small independent cinema scene. This welcoming surrounding gave me also the possibility, to meet Tamara the following day for a longer interview in the blossoming backyard of the Nala Hotel, where we went deeper into the topics of her auto fictional documentary.

What’s the story behind your film My Armenian Phantoms?

When my father died four years ago, I started looking back. I think trauma does that – it makes you return, search, try to understand. I began watching home movies, films in which he acted and photos of him, and somehow – it was almost like it took me by the hand – it led me deeper toward Armenian cinema, toward its “phantoms.” My father had acted in many Armenian films. It was like I had opened a treasure box. I felt the urge to explore it, clean it, show it to the world.

What began as something personal quickly grew. I realized I was facing an enormous body of work. People told me I was crazy to do it, but I felt a deep desire, a curiosity – and maybe, subconsciously, a need to claim my Armenian filmmaker identity. Being born in a place doesn’t automatically entitle you to represent its cinema. For instance, I grew up in Lebanon for 17 years – I know Lebanese cinema, but I can’t say I represent it.

What do you think it requires to present a certain cinema like in your case to represent Armenian cinema?

You have to understand it in an emotional way. I watched Armenian films as a child before I had left Armenia at age 12 and didn’t revisit those films for decades. But I remembered them – my emotions remembered them. After my father died, I returned to them when I was 40. At first, I focused on the aesthetics, avoiding the personal because the pain was too much. But my producer Céline encouraged me to let the personal in. She said, “Tamara, your written text is one thing, but when you talk, you only talk about your father.” It took me a year to accept that the father–daughter story had to be part of the film. That emotional connection shaped the film’s evolution.

Before the film screening at IFFI, you said the film seeks a dialogue between the personal and the collective. What do you mean by that?

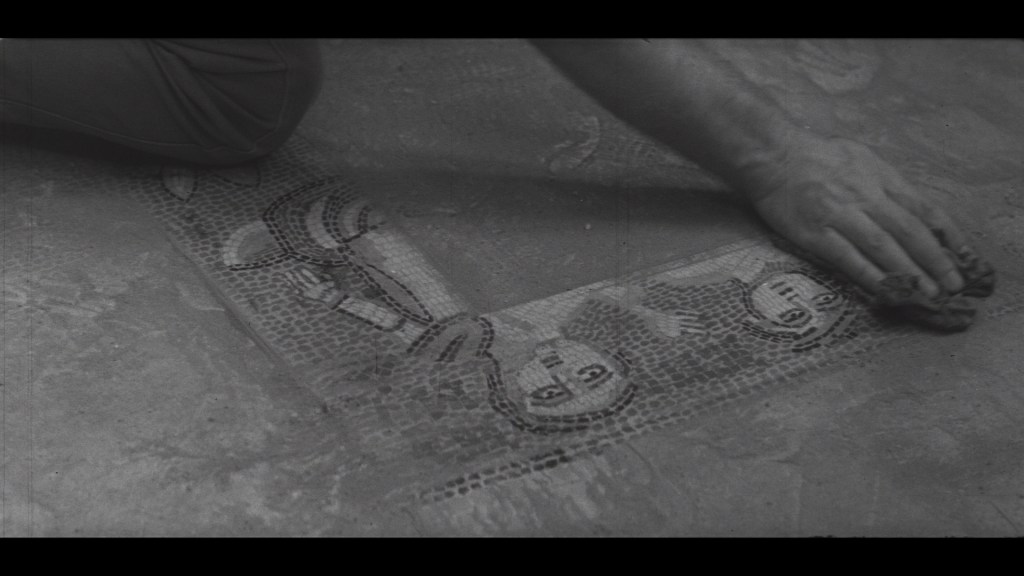

Once I allowed the personal in, I didn’t want to make a film just about me. Who cares about me, myself, and I? I always try to move from the personal toward the collective – toward Armenia, toward its history, its trauma, and its cinema. Armenian Soviet cinema, in particular, fascinated me. After 1922, the Soviets issued an order to create cinema in Armenia – like in Moscow or Tbilisi – because cinema was a mass communication tool. It was a way to convey ideology to the public.

They planned it systematically, for example, in one year they planned to produce two historical dramas, one children’s film, two comedies etc. It was systemic. I realized all that because I didn’t only watch the films, I also read the archives of scripts, discussions and censorship notes. That’s what I mean by collective. The personal led me into the historical, the common destiny.

Your film focuses only on Soviet-era Armenian films from 1924 – 1990, why only this period?

Partly because my father acted during that period, but also because I wanted to explore cinema under censorship. Armenian films of that time are both deeply propagandistic and incredibly artistic. I was interested to understand how creative cinema could exist amid censorship.

Also, there were no female filmmakers back then. I asked myself: what was it like for me, as a child and a girl, to grow up with images created only by men? That made me focus on this specific period.

Can you highlight any subversive films you found, which were made during that era ?

Yes, many. For example, Zangezur (Hamo Beknazaria, 1938). It’s a propaganda film showing a clash between Armenian nationalists and Soviets. On the surface, it supports the Red Army. But there’s a song in the film – one that I subtitled – saying „make the wolves leave.“ The wolves are the Red Army. These hidden messages – often in songs that weren’t subtitled – were a way Armenians embedded resistance in film.

The scriptwriter of Zangezur was executed by Stalin, the director nearly died. But they found creative ways to bypass censorship. Sometimes, I wonder how they got away with it – maybe the bureaucrats didn’t notice or didn’t want to notice. That tension – the line between state control and subtle subversion – was fascinating to me.

In the Q&A, you also mentioned that you discovered Sergei Parajanov, the most famous Armenian director worldwide, during your film studies in Beirut, while in Armenia, his work was censored. Would you say he has influenced your work in any way?

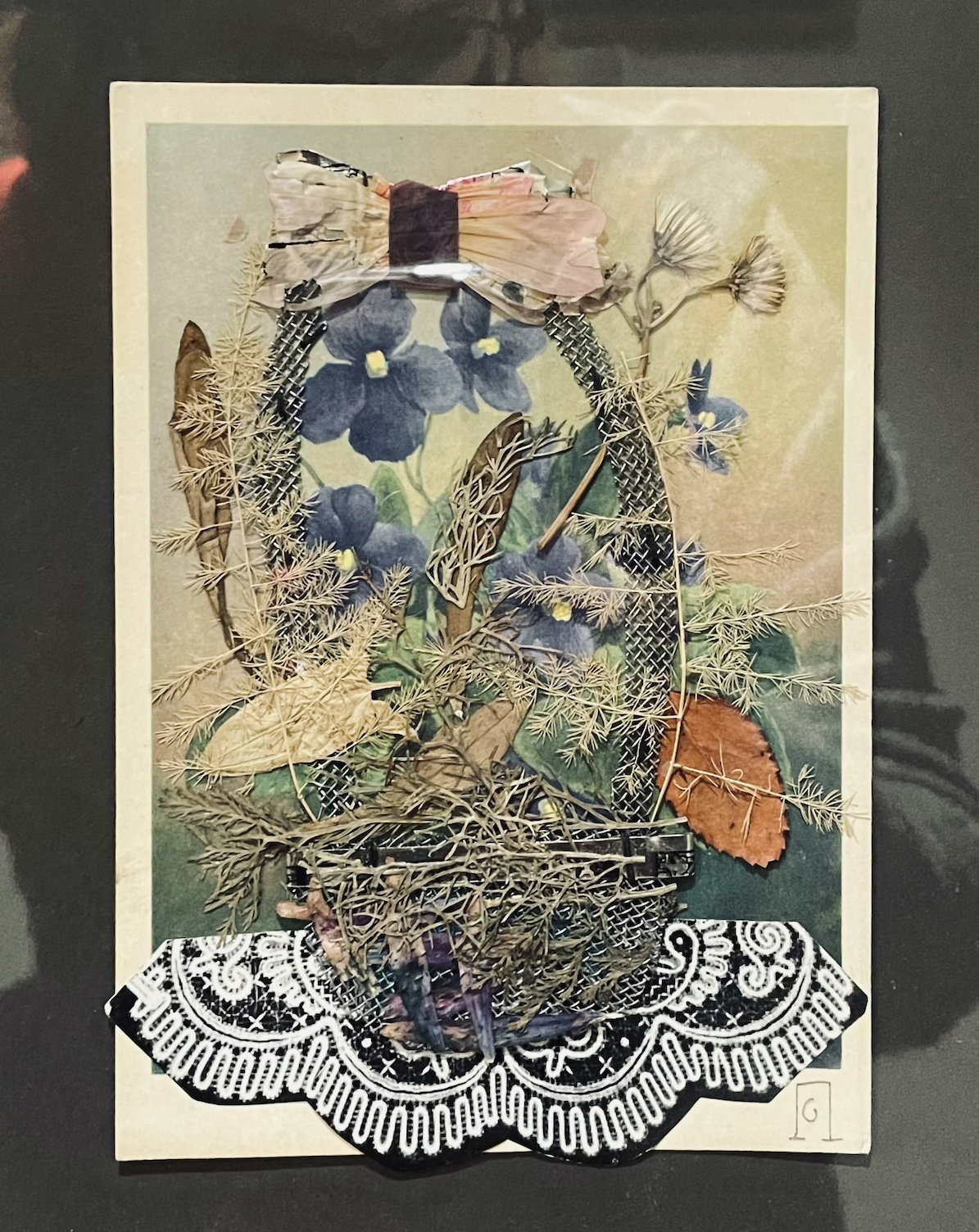

Parajanov blew me away. I remember thinking, „We have this?“. But then I remembered: I knew of Parajanov as a child. His museum was next to my house in Yerevan. The state had given him that house when he was already sick, near the end of the Soviet Union. He never lived there. The house became a museum. As kids, we used to play there. His collages amazed me.

In Armenian, we have a saying: „gna meri ari sirem” (Գնա մեռի, արի սիրեմ), which means „go die and come back – then I’ll love you.“ This is what they’ve done to so many artists. They tell you: suffer, disappear, and only then will we bring you back and shower you with love. That’s exactly what happened with Parajanov. They came to appreciate him too late. He was already on his deathbed when they suddenly began to say, “What a great filmmaker.” But he never got to live in that recognition. He had just started making a new film – he shot for two days (I’ve seen the footage) – and then he died.

Later, I found out that my grandfather personally knew him. There’s even a funny story: Parajanov met my grandfather in Ukraine and Parajanov was struck by how much they looked alike. He told him, “Are you a brother from another mother?” Then he took him to a field behind the studio and made him the most colorful, inventive bouquet of flowers – my grandfather always said it was the most creative and colorfully harmonious bouquet he’d ever seen.

Even if my cinema is not at all like his, he inspired me deeply. Parajanov is unique, he can’t be compared to anyone, not even within the world cinema.

Why is it important to you to write a history of Armenian cinema – especially now?

Armenia is at a critical political moment. It’s a country that has faced genocide, war, trauma – and still does. Looking back helps us understand, helps us heal. Armenian Soviet cinema has often been criticized by Armenians, but I almost felt the responsibility to say that there’s more to it. There are real works of art. I get angry when people say only Parajanov and Peleshyan were any good. That’s not true. Frunze Dovlatyan, Henrik Malyan, Hamo Beknazaria, Bagrat Hovhanissyan and many more, they were amazing.

We’re a small nation with a big cultural heritage. I wanted to create curiosity. Yes, there were lots of horrible propaganda films too – but also masterpieces.

And what about contemporary Armenian cinema?

There’s been a shift. Many women directors have emerged – especially in documentary, which is easier to fund than fiction. I think we broke a barrier, a metallic door. Today, Armenian women are pushing the cinema scene forward. We’ve become cultural ambassadors for this country in the world.

How does the diaspora influence Armenian cinema? And in general, would you say Armenian art is shaped more by diaspora than by locals as for better access to funding?

Many diaspora filmmakers come to Armenia, it is becoming an attractive land. Some do respectful, profound work – but many don’t. They treat Armenia like an exotic set. They criticize social issues like selective abortion without understanding the culture. I’m not justifying it, but there is a very tragic history behind this. If you’re going to tell these stories, you must dig deep. Be respectful. Understand the history first – don’t forget that everything has roots, everything has history.

Regarding funding, yes of course, countries like France or Germany have more funding opportunities than local Armenian funds. Luckily, for five years now there has been a number of co-productions that help films to exist.

Your grandmother was a film editor, and you’ve mentioned that editors – who were mostly women in Soviet cinema – contributed equally to the creative process as directors, yet often remain invisible. Would it make sense to rewrite film history to give editors the recognition they deserve?

Absolutely. It’s a very interesting thought and it makes sense. Some of the best editors in Soviet cinema were women, but no one know their names. I always highlight editors in Q&As. Because even today, they remain invisible. My editor, Olivier Ferrari, edited almost all my films. When we were selected for the Berlinale, I insisted he come. It was his first time representing his film at a festival. Editors are usually not invited to film festivals.

Do you also have some female film directors you look up to?

I like Chantal Akerman, her deeply poetic films. It’s her birthday today, she would have been 75 years old, she died too young. Also, Jane Campion, Dominique Cabrera. But it’s a tough question. There are not many from the older generations. My love is for old-school cinema, and sadly, there weren’t many women directors then – not just in Armenia, but globally.

In your film, your father seemed skeptical about you becoming a filmmaker as a woman. Did that change? Did you feel supported by him later on?

At first, both my parents were hesitant. They asked if I’d rather study political science or business. I said, “That’s not my world.” Once they saw I was serious, they supported me completely – even took a bank loan to fund my studies. My father saw himself in me.

I remember once, for a short film, I needed a train to shoot in, but of course I could never afford to rent a wagon. My father, who was a well-known actor, used all his charm to convince the Russian railway officials to help me. Thanks to him, they gave me a whole wagon for four nights for free: Yerevan–Tbilisi, Tbilisi–Yerevan. The entire film was shot in that train.

My parents were proud when I succeeded. And I’m proud too, I’m proud that I can inspire other women to believe it’s possible. Cinema is my way of life. It helped me through the most painful periods. Being here at the festival, screening my film, teaching a masterclass – this is a healing process for me.

There is a very beautiful poetic scene at the beginning of the film, where apples are falling from a tree into the ocean. What film is that from?

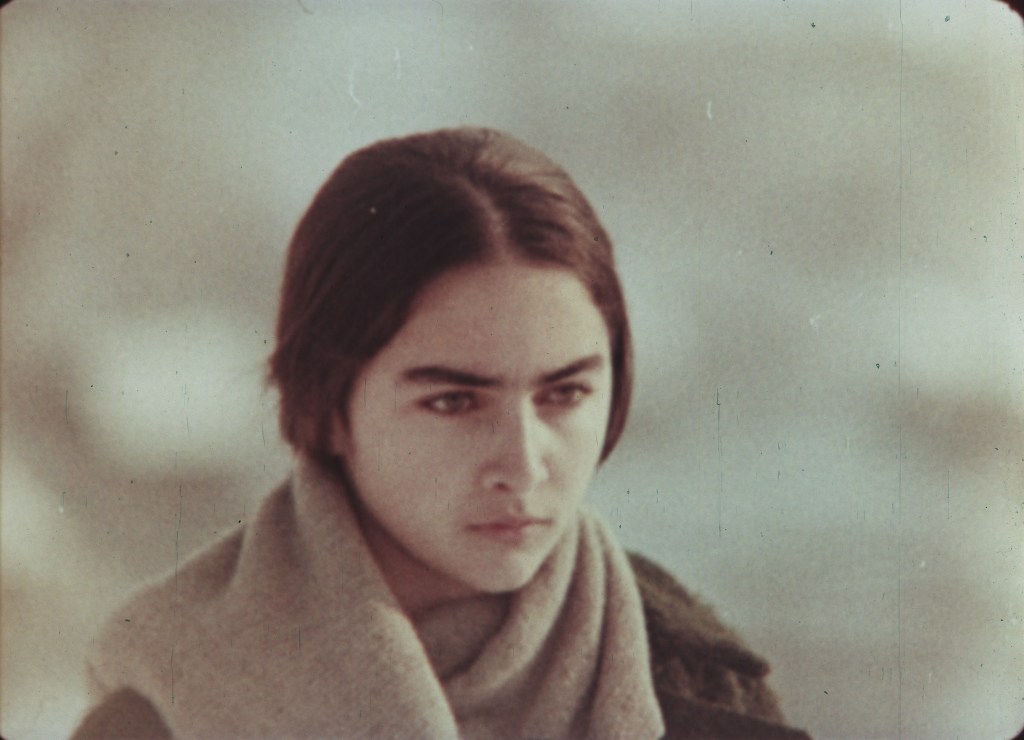

That’s from Nahapet by Henrik Malyan (1977). It’s the first film about the Armenian genocide. The scene is very metaphorical – the apples represent the victims and survivors of the Armenian genocide, and how they were spread into the world. Armenian films often use metaphors to escape censorship.

Do you plan to continue working with the film Armenian film archive?

I think I’m done for now with Armenian cinema archives, but I’ll continue exploring archival material. I’m interested in Soviet-era newsreels – daily life chronicles. Not cinema per se, but documents of a way of life. There’s something almost hallucinatory about them.

Finally, as this year’s festival’s motto is “The Past Is Now” – and your film is titled “My Armenian Phantoms” – what is it that fascinates you about the haunting image of the past?

I think it’s because the present isn’t so fascinating. Why go back? The need to dig into the past, to bring it out, is because – even if it was complicated, regime-controlled, and all that – there was still something interesting about it, something creative.

But generally, for me, the present isn’t very exciting. I do think there is an interesting youth today, a very passionate youth. But I also see a very complicated youth – completely lost –some destroy what’s around them without even realizing what values are, what ethics are; I’m not really criticizing them; it’s not their fault; and while others are fighting, they are aware, they try to be. I think the world we live in is quite messed up – with all these wars and genocides – imagine, in 2025! What on earth? Haven’t we learned enough from disaster, from war?

I feel almost sad for the youth. I think the past holds something very rich that today we are trying to grab onto, to give meaning to. I’m quite pessimistic about the present.

And the future?

The future – no. I don’t want to be pessimistic about it, because I also have children, and I want to leave them a better world. Maybe that’s also my way of fighting the present: by shaping the future. Me and many others – we try to build something better so our children can be proud to live in it. That’s important: to change things, to limit things, to explain, to talk, to teach…

| Brigitte Egger

Tamara Stepanyan

A film director born in Armenia, Tamara Stepanyan moved to Lebanon in the early 1990s and continued her studies at the National Film School of Denmark. She now lives in France and is considered to be the new voice of contemporary Armenian film. Her feature film, Embers (2012), premiered at the Busan International Film Festival in South Korea. She directed Those from the Shore (2016), best documentary at the Boston Film Festival and the Amiens Film Festival. Village of Women (2019) participated in over 30 festivals and received 9 international awards and an étoile de la SCAM. She is currently in post-production on her first fiction film, Save the dead, shot in Armenia, with Camille Cottin and Zar Amir Ebrahimi.

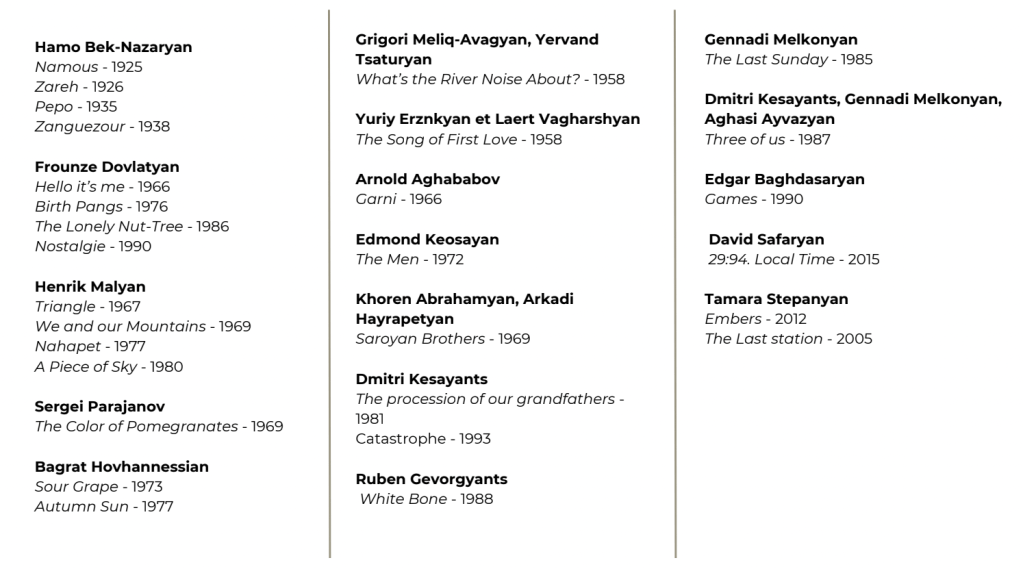

List of Armenian Films in My Armenian Phantoms