Identity is a recurring theme in contemporary art. Shaped by society, culture and politics, people have always been concerned with the question of their ’self‘ in relation to the other(s). Yet identity – as much as humans try to fix it – is characterised by fluidity and constant change. The current exhibition of the Büchsenhausen Fellowship Programme for Art and Theory 2023-24, entitled The Secret Life of Plants and Trees, explores such growing antagonisms and shifts in identity politics. At Kunstpavillon Innsbruck, the three fellows Agil Abdullayev, Tatiana Fiodorova-Lefter and Hori Izhaki present their artistic research works, all involving ‚botanical agents‘ to deconstruct and reconstruct various discourses on identity.

We had the opportunity to have a conversation with Tatiana Fiodorova-Lefter, artist from Chisinau, about her research project on the decolonial questioning of (post)Soviet identity formation, and how all this is linked to two central plants: the corn and the nettle.

komplex: Tatiana, your long-term research project carries the title IN RUINS/’IN SEARCH OF IDENTITY‘. Why is identity such a central topic in your artistic work?

Tatiana Fiodorova-Lefter: It’s because my own identity has gone through periodic crises that have required me to re-evaluate myself. The collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s had a profound effect on the lives of many people, including myself. Born and raised in Soviet Moldova, I experienced changes that affected every aspect of my life and my identity. When I experienced a second identity crisis in 2022 with the outbreak of full-scale war in Ukraine, I felt immense pain and disorientation. I began to actively study the historical and political contexts of the conflict in order to better understand its causes and consequences. The exploration of identity has become a long and intensive process for me.

The project ‚IN RUINS/IN SEARCH OF IDENTITY‘ delves into what lies beyond the Soviet and post-Soviet period. In order to fully grasp this process, a broader approach is essential. This includes not only analysing the Soviet project with its imperialist and colonial dimensions, but also studying other global actors and their roles in influencing and shaping our region. Therefore, the central question of my project is less about my personal identity and more about territory and belonging. I focus on historical perspectives of territories and their evolution over time. My research aims to uncover how political, social and cultural dynamics shape collective identities within different geographical contexts. By exploring these themes, my project seeks to illuminate the complexities of post-Soviet identity and contribute to broader discussions on spatial belonging.

How old where you, when this national territory changed?

I had just finished high school and was about to start university. Suddenly, it became another country, totally. The post-Soviet era was a time of uncertainty and change. Like many teenagers of that time, it marked my first experience of finding myself and understanding my place in a new society. When I left school, I was faced not only with the need to choose a career, but also with the realisation that the world around me had changed fundamentally. I felt that familiar landmarks and stereotypes had been overturned, forcing me to rethink my beliefs and values.

My generation in Austria has never experienced such a shift in national territory, I cannot imagine how this must be like… What changes and challenges did you face during this transition period from USSR to Republic of Moldova?

The period of upheaval and the collapse of the Soviet Union was a very challenging time for everyone due to the radical changes in our country. Many contradictions emerged. On the one hand, after the dissolution of the USSR we gained freedom of expression, there were no political prisoners, social life became more democratic and there were more opportunities to travel abroad. On the other hand, this period was characterised by economic challenges related to the establishment of a new neo-liberal economic model. The collapse of the unified economic system led to economic instability and forced many former Soviet republics to seek new paths of development. This was accompanied by devaluation, inflation and low wages. National and ethnic tensions also escalated, leading to the Transnistrian conflict, followed by several months of war. In the conditions of political and economic instability, many began to leave the country temporarily for work, and later to settle permanently. Under these conditions, after the war, I graduated from a college in Transnistria and then went to university in Chisinau.

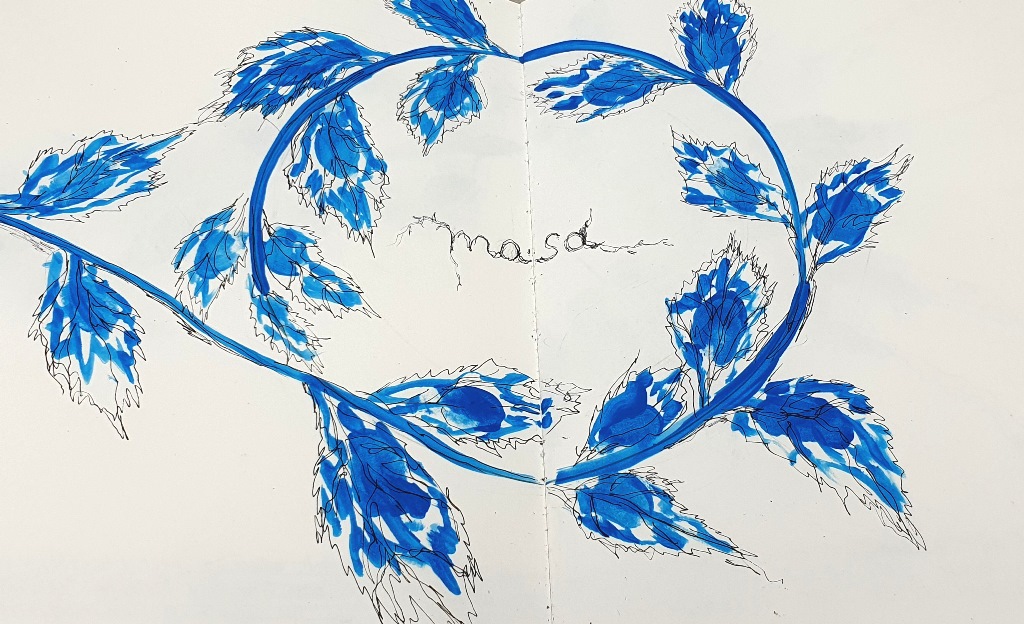

A special element as part of your exhibition is your artist book ‚Urzica‘ (nettle), dedicated to a central plant in your project, the nettle. I found it interesting that the story starts with a page, where you see nothing but a single nettle leaf and on the next page a single fingerprint – what’s the link between the nettle and your identity?

If you notice in this book, all the drawings of nettles are based on my fingerprints, not just the first one. I used my fingers like children to make a blue pattern and then I drew the nettles over it, so in a sense I start my identity through these nettles.

The book tells the story of my relationship with the nettle plant from my childhood. I agree with the concept that identity is fluid and changes over time depending on how we relate to our memories and life changes. At this stage I am revisiting my childhood and memories to reconstruct my identity. As for identity, I have tried not only to look for post-Soviet traces, but also to go beyond them to show the connection of belonging to this territory in terms of ethnic roots, traditions and also connection to the land.

It was interesting for me to see that these traces came from my childhood connection with post-Soviet identity but also with my other identities. My mother is from Ukraine, from the Odessa region, and my father is from Moldova. They both came from villages, but later moved to Chisinau. I was born and raised in the city. I didn’t have any connection with the village, just a few relatives. Symbolically, the nettles of my memories return to those roots – to my mother, my father and also to my grandmother, who used to cook porridge from nettles in the village. I remember that when we used to go there with my family, when my father was still alive, my grandmother would prepare this nettle dish. It was something strange for me, because as an urban Soviet child we didn’t have that kind of food. It was strange, unusual, but tasty. Later, my mother took the recipe and started making the same dish. She used to take me with her to pick nettles in the spring. I remember walking through the city of Chisinau, it was quite difficult for us to find this plant.

You also prepared nettle porridge in Innsbruck and served it to guests at Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen. What’s your impression of how the nettle plant is perceived in the Tyrolean culture?

During my stay in Innsbruck, when I arrived in October, I started walking in the mountains. The first thing I found was a nettle, and when I walked for a long time I understood that there are a lot of them around, not like in my home town, because Innsbruck is so connected to nature, you have a lot of green.

When I came back in spring, it was the perfect time to collect nettles and make this porridge, which we ate together at an event in Büchsenhausen. With the support of Andrei Siclodi, curator of the fellowship programme, we also prepared the traditional corn dish Mămăligă. It was an act of solidarity on his part, as we both have common traditions and share many cultural similarities, including this dish, as he immigrated to Austria from Romania in his youth.

During the event, I also talked to some of the locals about the nettle. I understood that for them it was something new, it’s not a tradition here to prepare food from nettles. But I know from my area that it comes from the villages and goes back several hundred years ago, when it was hard for people to survive after winters. Those people ate nettles because they were rich in vitamins.

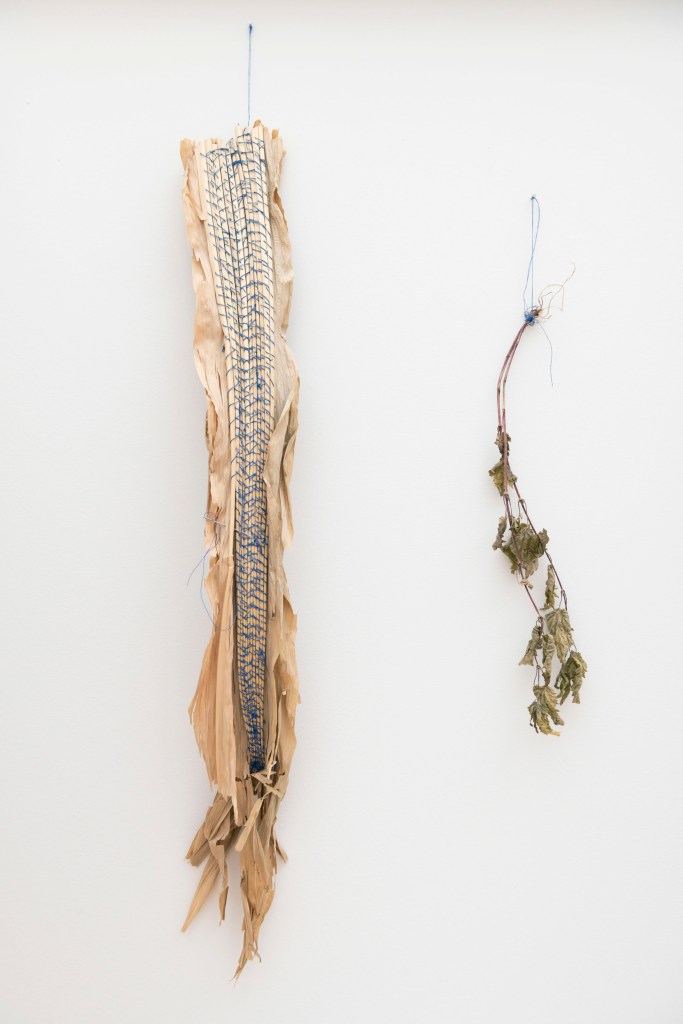

In my artistic research I also focus on another plant: corn. This plant arrived in Moldova only 200 years ago. Today, it represents a cultural tradition and is our most important crop, used, among other things, to prepare the traditional dish Mămăligă. We could even consider corn a national heritage, but it doesn’t fully encompass our identity. Instead, it has become part of our identity over time, although its historical origins go back to the Ottoman Empire, which introduced corn to our region. Even earlier, corn originated in the Americas and spread to all European territories with the rise of capitalism. Thus, collective identity, including my own, is not defined solely as post-Soviet; it bears many complex traces and influences.

Why did you choose the color blue instead of green for the nettle? Overall blue seems to be a central colour in your exhibition…

Blue was crucial for me, not only in the artist’s book, but also in the construction and other elements. Firstly, the construction – the ‚changing room‘. It serves as a hybrid of identities, based on the reconstruction of a Soviet changing room that was popular at lakesides and seashores, as well as a Moldavian peasant house.

I painted it on the outside with this blue colour that is common on the walls of houses in the countryside of Moldova.

Similar to the corn, these blue facades in the countryside now form the national identity of Moldova. Another interesting fact is that this special pigment (blue), which we used to cover walls, is called in Russian language „синька“. In Soviet times, lime with the addition of „синька“ was used for a long time to preserve the white colour and so that it would not turn yellow with time, and later began to be more blue. It was also used as a disinfectant. Continuing the study of the formation of cultural codes, it is necessary to note that the dye was invented in Germany in the 80s of the 19th century and was imported to our region from the GDR and India during the Soviet period. It is an interesting connection in this context, as it also parallels the history of imported corn.

I found it interesting how you combine the urban socialist elements and the rural folk elements in your work. Apart from the colour blue, you work a lot with shades of grey, which obviously goes back to socialist modernist architecture – I’m thinking especially of the paintings on the wall outside the changing room…

These coloured paintings belong to the second part of my research. My project is structured like a book: I have the introduction, the first chapter, the second chapter and the conclusion. The Changing Room is the first chapter, Shades of Modernity is the second, including the series Shadows of Modernity/Shades of Grey. The first chapter was about how ‚I decolonised myself‘ through my personal memories and identities. The second chapter is about how ‚the whole world is decolonising itself‘. When I started researching art, I wrote a little poem about decolonization:

I decolonised myself

You decolonised yourself

He decolonialised himself

She decolonialised herself

We decolonialised yourself

They decolonialised themself

The whole world decolonises itself.

The series Shadows of Modernity/Shades of Grey shows the grey colors of socialism, the grey colors of capitalism – different paradigms in which we lived or live in.

The second chapter also includes your work called ‘Two faced modernity’, displaying a stone which is half black and half white. How is it related to this duality?

During my stay in Innsbruck, I found this stone on the bank of the river Inn. This stone has an unusual structure. Nature has divided it into two parts: half of it is light, half of it is dark. This made me think about the duality of our world and the fact that our modernity is always dual, thinking about the lightness and darkness of modernity. I also saw in this stone the image of a two-headed Janus, facing the past and the future. I thought it was a good metaphor for the exhibition. This is the central element of the exhibition and my thoughts about the world and its imperfections and contradictions.

Related to this, you find another object in the exhibition space, it’s called ‘Roots and Concrete’ and shows our contemporary situation: When we were born, we came into the world as humans who are directly connected to nature, but growing up in a society, we live in different paradigms like capitalism, socialism, etc. Our society constructs artificial things within us and our roots, like the roots of a plant, we are forced to fit into it. For me it’s a contradiction, we are so far away from our nature as human beings. In the 20th century, under both socialism and capitalism there was active exploitation of natural resources. I would like to ask how we can get closer to nature? Do we have a chance to build a just society? Do we have a chance to live in harmony with nature?

Speaking of our relationship with nature – you mentioned that you grew up in the city of Chisinau, far from the rural life. How did you personally find your way to nature?

I started working on this issue three years ago during the pandemic. I grew up as an urban person with no connection to nature. But during the lockdown I realised that I had to run to the village because I had no access to parks or anything. In the village I started doing a lot of different things. I started working with plants, learning how to take care of them. During these three years of my connection with the village, I developed this practice and also made a small garden of nettles. Somehow it was important for me not only to collect nettles but to grow them myself, it seemed good to have them in my garden. I also started growing corn. I hadn’t had any experience of growing plants before, and I remember celebrating myself for growing corn, boiling it and eating it. It was a fantastic experience for me.

When I came to the countryside, I didn’t know how to be a village woman, but I had great neighbours, like Valya, who started to help me. They said, ‘No, no, no, not this way, you have to do it this way’. I also had a vineyard that needed looking after. I had to learn a lot about how to prune in the spring and then how to tie up the branches of the vines and spray them regularly to prevent disease, etc. The first year I almost didn’t harvest at all. I made a lot of mistakes: I sprayed the grapes at the wrong time, I cut the wrong branches. Nature taught me a lot about how to keep up with natural cycles and everything was done on time. Last year, I finally grew grapes, which turned out to be more than my family could use. And a new task arose: What to do with the grapes? My family gave them to relatives and there were also leftovers. How to sell them? I had to learn that too.

But that’s another nice thing in our villages: We don’t have fences between our plots, it’s all transparent, we watch each other what we’re doing, say hello and talk about our problems. In the city, in a five-storey building, I didn’t have that opportunity. It’s a different relationship with the neighbours.

As you just mentioned your neighbors – as part of your project in Innsbruck, you created a balcony outside of your studio in Büchsenhausen and got in touch with people passing by on the street. Was this idea connected to your experience in the village?

These practices are not directly related, but they flow from each other. In the countryside I liked being close to nature, and it’s the same in Innsbruck. This city is different from Chisinau; it is organically woven into nature. In the mornings I would wake up with a constant desire to go out of the studio mainly because I needed sunlight and the view to the mountains. I realized that my studio window has the potential of being a balcony as of its size, so I created this balcony, to be closer to nature. I used to bring tea and books. At the beginning, I didn’t have the idea to connect with people, I just wanted to go out and admire what is around me, but then I received quite wonderful reactions from the people on the streets, people were curious and started to speak to me.

I decided to put some signs on the window that explain what I am doing here, and I wrote that it’s a balcony, and I’m a Künstlerin. After this even more people approached me. That’s also how I met my future friend Theresa and started to practice ceramics with her. We met when I was drinking tea on the balcony. She is a supernice woman, more than 80 years old, she was very interested in what I am doing, so she invited me spontaneously to her place, which was only five minutes away to show me her balcony and her garden. At her house I observed she was ceramicist, she used to be a teacher for ceramics and has her own studio. I admired her practice and asked her to show me how to do it. After this, I started to make ceramic objects by myself, but these skills all came from Theresa, I didn’t have any experience with it before.

For me it was quite impressive that this balcony gave me the possibility not only to meet people, but to make friends and to learn a new practice. This balcony transformed my project, it became something more, like a participatory project.

| Brigitte Egger

The exhibition The Secret Life of Plants and Trees, curated by Andrei Siclodi, can be visited at Kunstpavillon Innsbruck until August 10th, 2024.

Find more infos on Tatiana Fiodorova-Lefter and her projects on her website.

Ein Gedanke zu “From Nettle Leaf to Identity – In Conversation with TATIANA FIODOROVA-LEFTER on Being ‚Post-Soviet‘”